Women rainmakers under attack for their ambition: combatting Tall Poppy Syndrome

By: Steve Schuster, [email protected]//March 29, 2024//

Women rainmakers under attack for their ambition: combatting Tall Poppy Syndrome

By: Steve Schuster, [email protected]//March 29, 2024//

As March concludes Women’s History month, two Wisconsin attorneys joined a national panel during an American Bar Association (ABA) March 20 webinar addressing Tall Poppy Syndrome.

The program, “Cutting Tall Poppy Syndrome Down to Size: Creating Work Cultures that Embrace Ambitious Women,” featured a nationwide panel of attorneys.

Milwaukee-based Emily Logan Stedman, who recently made partner at Husch Blackwell, was on the panel, along with Madison-based Attorney Michele Powers, who works as a leadership coach.

Other panelists were Paulette Brown with and Kate Harmon.

Brown was the first woman of color to serve as a president of the American Bar Association. Harmon is the current president of the Delaware State Bar and serves as a litigation team partner with Benesch, Friedlander, Coplan & Aronoff LLP.

All of the panelists are a part of an ABA subgroup, “Women rainmakers law practice division.”

What is TPS?

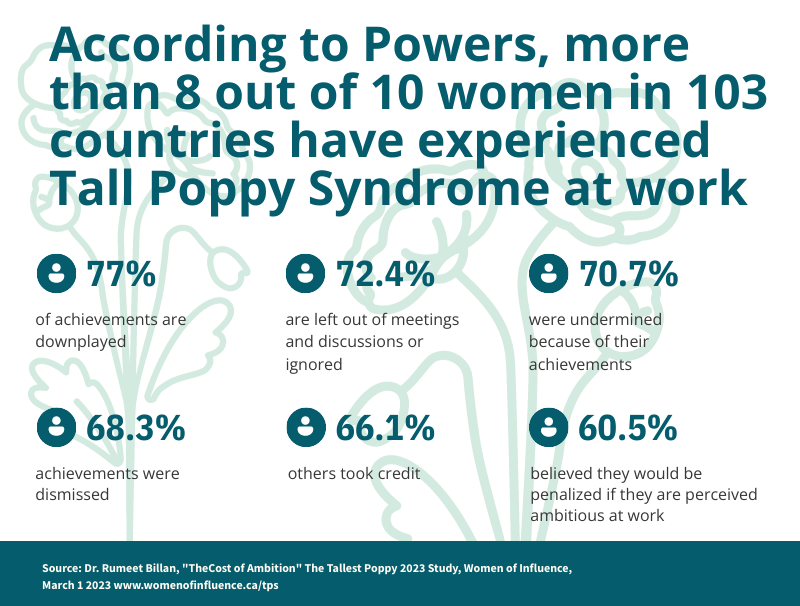

“Tall Poppy Syndrome (TPS) occurs when a people are attacked, resented, disliked, criticized, or cut down because of their achievement or success,” Powers said during the webinar.

The ABA webinar addressed how “tall poppy syndrome” impacts women in the workplace.

“I didn’t know there was a name for something I had experienced,” Powers said.

Stedman, Logan and the other panelists opened up to the audience, sharing their personal experiences as successful individuals who have been criticized or belittled in the workplace.

“This is nothing new. This is something women and sometimes even men do as others display outward ambition. We are now just giving it a name, so women know they aren’t alone when they experience this,” Stedman said on March 28 during an interview with the Wisconsin Law Journal.

Recognize!

The panelists described the damaging effects on women, particularly professionally and personally, and the importance of first recognizing, and then calling out, such behaviors.

Brown said during the webinar, “We have to have people who are willing to call things out when they see and hear it. I have reached a point in my career where I am very able to do it for others.”

Not everyone has that luxury, according to Stedman.

“I am a new partner. I’ve been a partner for three months, so I am very close to the associate ranks,” Stedman said during the Wisconsin Law Journal interview.

“I know from personal experience how difficult it can be to speak up and say anything that troubles you as an associate, given the hieratical nature,” Stedman noted.

“While I don’t think that will ever go away, you can create spaces. If an attorney is not comfortable calling it out in the moment, maybe there is someone else at the firm they are comfortable speaking to,” Stedman added.

Sometimes the cutting down happens online, not at the office.

Stedman noted a recent experience on social media when she was writing about the billable hour in a LinkedIn post.

“I recently got a negative comment on LinkedIn on how I must not appreciate life. They wrote, ‘I hope you don’t have children,'” Stedman said.

According to Stedman, this is the first time she felt like an online comment from a stranger was something that needed to be addressed.

“There is something going on here that’s more than just about me. At certain times it’s important to call it out because of the impact it can have on other people who watch it happen,” Stedman said.

How is TPS experienced?

According to Stedman, what stat resonated for her the most is that “as a younger female attorney, a lot of good change has happened. So, I have not directly experienced overt examples of this,” Stedman said, noting, “but can see where I internalized this expectation. Yes, I was pushed to achieve, not be too loud.”

“I think a lot of millennial women like me are taught to tone it down at work. That’s almost cutting ourselves down. We are doing the bias to ourselves,” she added.

Who is responsible?

Men in leadership positions were more likely to penalize or undermine women due to their success, Powers said.

However, women, are more likely to cut down peers or colleagues, Powers noted.

“From a personal standpoint, it’s happened to me many times,” said Brown, noting when she was an ABA president and news releases were distributed, others would take the spotlight.

Why do people ‘cut’ ?

According to Powers, research indicates both men and women “cut” others down for a number of reasons.

“The top drivers for it … jealousy, sexism or gender stereotypes (how you’re supposed to be as a woman) and a lack of confidence or an insecurity in the person doing the cutting,” Powers said.

According to Brown, people can be determined to not see others succeed when they feel threatened.

“When it happens it’s because that other person feels so threatened by you. Sometimes, there is nothing you can do about it because they lack a confidence in themselves,” Brown said.

“You’re not able to fix that other person’s problem because that other person needs some professional help,” Brown said.

Law Firm’s Toxic Culture

According to Powers, people sometimes think when someone is rising up, it’s taking away from their own careers.

Referring to an old adage, “Rising tides lifts all boats,” Powers said, noting “there is plenty to go around.”

Stedman said sometimes the good intention doesn’t always translate into reality.

“Firms sometimes think they are rewarding ambition by giving Women more to do. But by giving us more to do, is not always the substantive work. It’s the administrative, or women’s work,” Stedman said.

According to Powers, “Sometimes this requires a shift in law firms.”

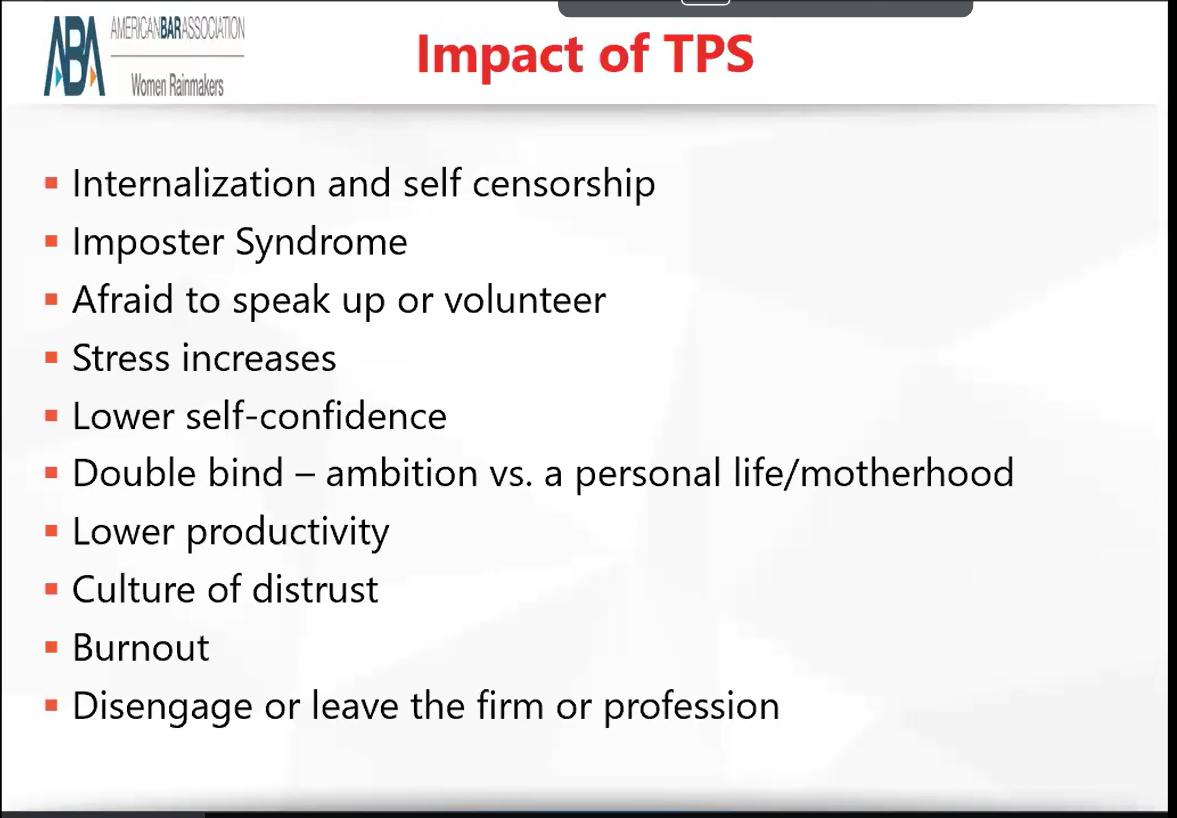

Impact

The discussion further addressed the impact this has on women’s professional and personal experiences and career opportunities within the legal profession.

During the webinar, Stedman shared how as a younger attorney she felt TPS right out the gate.

“I felt the need to fit a mold and ramp down my personality and ambition, because I felt different than the good ol’ boys club,” Stedman said.

Also during the webinar, Harmon noted how TPS exposure as a young lawyer shaped how she practices law today.

During a performance review, Harmon recalls how she was “TPSed.”

“I was a baby lawyer. This was my first law firm out of law school. I had only been there a few months. … I worked really hard to deliver a stellar work product. … I was excited to hear how I could be doing better as a lawyer and … the woman founding partner of the firm starts off with … “You have such a great personality … you’re just so likeable,” … I guess that’s a good thing to hear, but that’s not how I am as a lawyer. That isn’t my work product, those aren’t my accomplishments, or my achievements,” Harmon said.

The review, “really did shape how I practice … the persona that I bring with me as a lawyer in the room as a lawyer, it’s always in the back of my mind that I have to be this … cheerleader for the rest of the team, and whatever my work product is always going to be secondary to how I show up as a person,” Harmon said.

“I don’t think I can say that about any man I’ve ever worked with as an attorney in terms of that his persona would be prioritized over his deliverables,” Harmon added.

Education

Powers encouraged firms to “being more mindful about what they can do to create systems of support and education.”

Brown said education is key.

“Many organizations don’t even have a clue as to what Tall Poppy Syndrome is,” Brown said, noting “I think a lot of education is necessary.”

“I think people need to look internally and assess the trajectories of the women in their organizations and do a sort of backwards look to see how they have been treated,” Brown added, noting how men have been treated very differently than women.

“It’s going to have to be a real culture shift in organizations because they have been doing this for so long … sometimes you can’t move forward until you look at what you’ve done in the past with patterns and practices, ” Brown noted.

Stedman recalls being a second- or third-year associate at a big law firm and attending a CLE course in Chicago.

“One panelist said, “if you cannot be yourself at your firm, you need to get out and go out until you can be yourself.” That always stuck with me,” Stedman added.

Origins and solution

“I think people have been conditioned to think different ways,” Brown said.

Brown said, it’s learned behavior that has gone on for centuries.

“It has a lot to do with how people are trained to think about different things … you need to tear down some things and rebuild some structures,” Brown added, noting “historically people are taught to process and think differently.”

Stedman agreed.

“Either people didn’t realize it was a cycle … they didn’t want to break the cycle and others didn’t know how to break the cycle,” Stedman said.

“Education is so important that people understand what this is that we call it out by its name, so it can be adequately and substantively addressed,” Brown added.

Powers agreed.

“We grow up in the soup or the water. We don’t even realize how we are limiting ourselves or how we may actually be unintendedly limiting someone else,” Powers said.

Moving forward, Powers stressed the importance of “lifting each other up.”

“In terms of how we can shift the culture, in terms of how we parent not only our daughters, but also our sons. It’s important for all of our kids to see as women that we hold each other up, that we are defending each other and that we can do a lot to diminish this idea of women going after each other,” Powers added.

“By talking about it and brining awareness to it, we are breaking the cycles in our sort of spheres of influence,” Stedman said.

According to Stedman, there are ways to exercise autonomy in small spaces that will have a larger impact.

“I think it will change the profession from the bottom up,” Stedman said.

During Thursday’s interview, Stedman added, “It was encouraging to see women share so openly about their experiences. That is one thing that is changing, how much more comfortable we all are sharing about these things and bringing on change.”

Best Practices

According to Powers, speaking up and seeking support are among best practices.

“We need to normalize the fact that it’s OK to ask for support,” Powers said, noting the importance of finding others within the workplace where it’s safe to share success.

“There are amazing women who are mothers who are also amazing trial attorneys, and they are really at the top of their game,” Powers said.

Legal News

- Wisconsin attorney loses law license, ordered to pay $16K fine

- Former Wisconsin police officer charged with 5 bestiality felony counts

- Judge reject’s Trump’s bid for a new trial in $83.3 million E. Jean Carroll defamation case

- Dozens of deaths reveal risks of injecting sedatives into people restrained by police

- The Latest: Supreme Court arguments conclude in Trump immunity case

- Net neutrality restored as FCC votes to regulate internet providers

- Wisconsin Attorney General asks Congress to expand reproductive health services

- Attorney General Kaul releases update at three-year anniversary of clergy and faith leader abuse initiative

- State Bar leaders remain deeply divided over special purpose trust

- Former Wisconsin college chancellor fired over porn career is fighting to keep his faculty post

- Pecker says he pledged to be Trump campaign’s ‘eyes and ears’ during 2016 race

- A conservative quest to limit diversity programs gains momentum in states

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula