AG opinion not just about high-capacity well permits

By: DOLAN MEDIA NEWSWIRES//June 22, 2016//

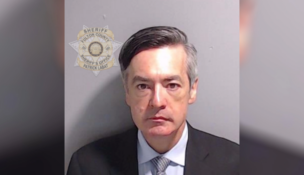

In what industry representatives hope is a sign of more good things to come, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources is streamlining its high-capacity-wells policies in response to Attorney General Brad Schimel’s May 10 formal opinion on 2011 Wis. Act 21’s limits on agency authority.

Specifically, the DNR concurs with Schimel that the agency lacks authority to require cumulative-impact analysis as a condition of granting a permit for a high-capacity well. The previous perception that the DNR needed to evaluate cumulative impacts, an analysis they acknowledge was beyond their capabilities, resulted in hundreds of well applications being sent to regulatory purgatory.

DNR reinstates old high-capacity wells policies

Industry representatives are hopeful that permits will now be issued in a timely manner, and without expensive and unauthorized conditions calling for the use of monitoring wells and cumulative-impact analysis. The polices that the DNR sets forth on its web pages gives them reason to be optimistic.

When reviewing permit applications, the DNR will limit its analysis to criteria enumerated in the statutes, such as whether the proposed high-capacity well will be near trout streams or other exceptional resource waters, will be likely to adversely affect public drinking-water wells or groundwater resources, or will threaten public safety.

For projects that fall into at least one of those categories, the DNR will only impose conditions related to location, depth, pumping capacity, rate of flow and ultimate use. Notably, wells that do not any of those boxes will be approved as requested. The DNR expects most applications for high-capacity wells be reviewed within 65 business days.

Any well approvals issued since Act 21’s effective date of June 8, 2011, will be reviewed by the DNR to uncover any conditions that might be inconsistent with the new policies. But it will be up to the permit holder to contact the DNR.

DNR officials’ “new” protocols for reviewing applications for high-capacity wells are essentially the same ones they followed before the courts and agency found implied authority to expand DNR’s reach to matters that, like cumulative-impact analysis, appear nowhere in the statutes. Act 21 was enacted with the clear intent to roll back what was becoming agencies’ implied ability to exercise their authority without limits.

Act 21 and the AG opinion applies to all agencies

The Schimel opinion rests on 2011 WI Act 21, which requires agency mandates to be “explicitly required or explicitly permitted by statute or by a rule.” Rules, in turn, must also arise from clear statutory authority. Thus, regulatory programs are adrift without legal authority, and thus invalid and unenforceable, unless they are firmly anchored to explicit statutory directives.

In a May 17 opinion letter published in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Schimel provides a basic civics lesson for the paper that elected officials, not agencies, make the law. “This conclusion is buttressed by (Act 21) which set parameters on state agency rule-making. Act 21 provides that state agencies, including the DNR, only can issue new rules and impose permit conditions when the Legislature has granted agencies explicit authority to do so. In addition, the Wisconsin Supreme Court has explained that state agencies are the creation of the Legislature and thus only have those powers that are expressly granted by statute.”

The AG opinion is mainly about high-capacity wells, but the limits on agency authority apply to all agencies and all programs. In essence, the requirement for explicit authority overturns decades of expanding court and agency opinions relating to implied authority.

That is, the word explicit by definition excludes implicit, making any agency programs resting on implied authority suspect. In that regard, the key pronouncement from Schimel states:

Act 21 makes clear that permit conditions and rulemaking may no longer be premised on implied agency authority. AG Opinion ¶ 29

The AG Opinion is significant, but consistent with prior positions taken by the AG’s Office, the DNR and by the court in the New Chester case. The New Chester case involved the DNR’s imposition of monitoring wells as a condition to obtaining a permit for a high-capacity well. The court threw out the conditions, finding:

Thus, under the plain language of (Act 21), agencies cannot rely on implied authority to impose conditions. Rather, those agencies must seek amendment to a statute or promulgate a rule. New Chester Dairy v. DNR, No. 14CV1055 (Wis. Cir. Ct. Outagamie Cty. Dec. 2, 2015), pp. 5.

Did someone mention DNR’s Public Trust Authority?

Many people continue to wrestle with the consequences of Act 21’s elimination of implied agency authority, and its long-needed overturning of inconsistent court decisions and related agencies programs. Yet, although perhaps less noted, there is another sweeping side to Act 21 that is also dealt with in the Schimel opinion. That is, explicit statutory authority is now a legal prerequisite to any delegation of Wisconsin’s public trust authority.

Wisconsin’s Public Trust Doctrine has been greatly expanded by the courts over the years to give the DNR virtually unlimited authority over the “waters of the state.” Yet, this constitutional authority resides solely with the legislature and can only be transferred to agencies through clear legislative delegation. Under Act 21, that delegation must be explicit in the statutes.

An important conclusion by Schimel set forth in his opinion relates to this point:

In Lake Beulah, the Supreme Court concluded that the Legislature had delegated broad public trust authority to the DNR for the purpose of regulating high-capacity wells. However, I conclude that, although DNR’s public trust authority has been expanded by the courts beyond the plain language of the Wisconsin Constitution, Act 21 restricts that authority by withdrawing the DNR’s ability to implement or enforce any standard, requirement, or threshold, including as a term or condition of a permit issued by the agency, unless explicitly permitted in statute or rule.

Schimel goes on to note that “therefore, much of the Court’s reasoning in Lake Beulah, including the breadth of DNR’s public trust authority discussed below, is no longer controlling.”

While there is ample consternation over the recent rollback of agency authority, the political solution lies where it always was intended; that is, the Legislature can fill any holes by enacting laws that explicitly provide agencies with whatever authority might be deemed lacking. There are many who believe, however, that administrative agencies are still not wanting for power.

Legal News

- Milwaukee’s Common Council now has the most African Americans, women and openly LGBTQ members ever

- Office of School Safety Provides Behavioral and Threat Assessment Management Training Ahead of 25th Anniversary of Columbine Shooting

- Wisconsin Supreme Court to hear arguments in Democratic governor’s suit against GOP-led Legislature

- Lawsuit asks Wisconsin Supreme Court to strike down governor’s 400-year veto

- Wisconsin man pleads not guilty to neglect in disappearance of boy

- ACS Selects University of Wisconsin Law School’s Miriam Seifter for 2024 Ruth Bader Ginsburg Scholar Award

- People with disabilities sue in Wisconsin over lack of electronic absentee ballots

- Wisconsin Republicans ignore governor’s call to spend $125M to combat ‘forever chemicals’

- Native American voices are finally factoring into energy projects

- Steven Avery prosecutor Ken Kratz admits ‘mistakes were made’

- Colombian national extradited to Milwaukee faces International narcotics-trafficking conspiracy charge

- MPD: Milwaukee homicides down nearly 40 percent compared to last year

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula