Changing order in the court

By: Erika Strebel, [email protected]//April 1, 2015//

Plaintiff, defense attorneys adapting to discoveries in social science research

As fewer cases make it to trial and social-science research undermines old notions of how jurors make decisions, lawyers are finding that they are spending less time in endeavors once deemed essential to their profession.

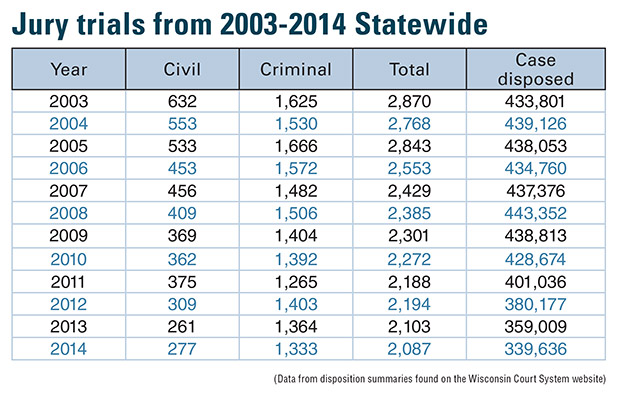

David Hansher, a Milwaukee County Circuit Court judge with more than 20 years on the bench, said cases had a much better chance 10 to 15 years ago of being brought to trial. According to online records, state courts took on 632 civil jury trials in 2003. By 2014, the number had dwindled to 277.

Milwaukee County Circuit Court Judge Christopher Foley said he thinks that the expense of courtroom battles is part of the reason fewer cases are going to trial. He said he often knows from the beginning that a case can be settled. Yet, it might still take spending $7,000 to $8,000 in discovery before that conclusion can be officially reached.

Expert witnesses are particularly expensive. Foley said he has seen jurors’ eyes fill with incredulity when they find out how much an expert witness is being paid to testify.

“It is so crazily expensive to litigate cases, from my perspective,” he said.

Ann Jacobs, a personal-injury lawyer and president of Wisconsin Association for Justice, a group that mainly represents trial lawyers, echoed Foley.

“There’s been a change in the cost of obtaining reports from treating doctors,” she said. “They have gone up substantially, and it definitely has an effect on the money your clients can recover.”

In another fundamental change, Hansher said, courts can now order parties to attempt mediation before going to trial. Hansher said judges began ordering more mediation, in part, as a way to prevent courtroom proceedings from eating up all their time. In Milwaukee County, Foley said that almost all — about 90 percent — of large claims civil cases are ordered to mediation.

The turn to mediation, which took off in the mid-to-late 90s, has left an profound imprint on the practice of law. Ralph Weber, a lawyer who teaches trial advocacy at Marquette University Law School, cited mediation as the single biggest reason for the decreasing number of jury trials.

“I believe as a result of its effectiveness, people have opted to go with the guidance of a mediator to get a better handle of the risks of going forward,” Weber said. “It’s a risk-reward calculus for both defendant and plaintiff. The most effective mediators play a role in offering an assessment of each side’s strengths and weaknesses as part of a risk-reward analysis.”

Foley agreed that mediation has its benefits.

“It’s less expensive, lets litigants control their own destiny and resolve our disputes in manners that are at least reasonably acceptable,” he said.

Stephen Meyer, a criminal defense lawyer in Madison, said mediation’s close cousin – arbitration – has come to be seen as nearly indispensable in attempts at protecting business interests. Meyer, whose career spans more than 30 years, said company executives nowadays tend to think of juries as something they cannot control and thus should avoid.

Arbiters, with their training in legal matters, are often perceived as being safer bets. The change has given lawyers fewer opportunities to employ the same sorts of arguments and techniques that they would in a courtroom.

To be sure, lawyers play a prominent role in arbitration and mediation proceedings. But, unlike the lawyers of previous generations, they are not building up a reserve of trial experience.

“One of the hardest parts of not going to trial as often is keeping trial skills well-honed,” said Jacobs. “So, you have to be much more diligent in keeping those skills sharp.”

Christopher Stombaugh, a trial lawyer who started his career in Platteville, agreed.

“You have lawyers who are less prepared to try those cases and less equipped to know how ordinary people think about anything,” he said.

Losing touch?

Meyer is concerned that the public might lose touch with the legal system.

“The juries encourage community participation,” he said. “It educates the community about how the legal process works, and I am confident that those people who participate have a greater appreciation for the system. And the less people have participated, the less understanding you have, and that corresponds with a diminishing respect for the process.”

Even among lawyers who do regularly take cases to trial, chances are they are not presenting arguments in the same way they probably would have 10 years ago or more. Recent scientific research into the workings of the human mind has brought about gradual change in lawyers’ comportment before juries and judges.

“Going back to Plato, we have accepted the notion that if we tried hard enough we can make decisions solely on reason,” Weber said. “The last instruction that jurors get before they deliberate is ‘Free your minds of all sympathy, feelings and bias, and let your verdict speak the truth, whatever the truth may be.’”

But, as it turns out, that’s not how the human mind works.

“You have to start with an appreciation of how humans really make decisions and then build your trial presentation on that reality as opposed to clinging to the myth that we can be solely rational decision-makers,” said Weber.

Mind games

In recent decades, research in neuroscience and behavioral economics have found that it’s impossible to separate reason and emotion, Weber said, and that the cerebral cortex works in tandem with the subconscious to make decisions.

“That raises profound questions for a system of dispute resolution that, on its face, is predicated on a devotion to rationality,” he said.

For example, Jacobs said she was trained as a young lawyer to ask close-ended questions during jury selection. The original notion, she said, was that those sorts of questions forced respondents to commit to a belief and follow it.

That has changed, Jacobs said, under the influence of recent social-science research. Now open-ended questions, with their allowance for free elaboration on various topics, are perceived to be a much better way for lawyers to delve into jurors’ minds and gauge the chances of receiving an impartial hearing.

“There were reasons why certain techniques developed without research,” Jacobs said. “We’re learning some are really effective, and others are best forgotten.”

The recent psychological research has become the foundation for a new firm: Stombaugh, Smith and Co., Towson, Md. The firm, which Stombaugh helped found, is a joint venture among three companies: Smith, Gildea & Schmidt LLC, Next Research LLC and Next Trial Innovation LLC.

Next Research is the company’s research arm and will help develop and test trial techniques. Next Trial specializes in training trial lawyers.

Stombaugh said he has always been interested in cognitive science and understanding how people make decisions. He said he wants to make sure trial lawyers throughout the country can take advantage of the latest research.

“What we want to do is continue to train lawyers in ways that will help them tell the true story in ways that will be heard,” he said. “And not just heard, but interesting to the hearers because these poor jurors, they’re like prisoners. They have no choice but to be there.”

End goal

The end goal isn’t entertainment or even making sure trial lawyers win more cases.

“What we’re trying to do, why this even matters: it’s the concern that we have in terms of community safety, in terms of juries actually being empowered …” Stombaugh said. “If the lawyers aren’t giving them the tools to do that, we’re going to have a lot of verdicts that disincentivize safety overall.”

Aside from trial techniques, social science research is also affecting lawyers’ reliance on eyewitnesses. Researchers in the past decade, Weber said, have devoted a great deal of time to studying how human memory works — or, in some cases, doesn’t.

“There is this idea that your mind takes a photograph or perhaps takes a video tape and is unchanged over time, and thus eyewitness testimony is accepted as accurate,” he said, “But scientists have found that memory is changed every time it is accessed.”

In one example, the cognitive psychologist Ulric Neisser handed out a questionnaire to 106 students in one of his classes the day after the explosion of the Challenger space shuttle in January 1986. The questionnaire asked the students about a host of matters, including what they were doing when they heard about the explosion and whom they were with.

Two years later, Neisser gave the questionnaire again to the same students and found that their memories had changed greatly. Even more telling, he reported, they expressed greater confidence in their later memories than those they had relayed the day after the explosion.

Only one state has officially acknowledged the ramifications of the research. Since 2012, the New Jersey Supreme Court has instructed state trial courts to inform jurors that eyewitness evidence may not be reliable.

“It’s an example of the courts recognizing, ‘Wait a minute. The way juries work , the way human minds work has been different than what we’ve been assuming … We need to instruct jurors accordingly,’” Weber said.

Not everyone is impressed.

Meyer, who has been practicing law for 36 years, said he is skeptical of the some of the conclusions lawyers have drawn from social-science research. For his part, he said, the latest findings have had no noticeable effect on the ways he goes about being a trial lawyer.

“If that’s considered social-science research, I’ve spent a total of five minutes in the last 36 years considering social-science research on jury behavior,” Meyer said. “I think it is more important to live life — get out of the ivory tower and out of the law office and read to understand the human experience.”

The courtroom of the future

During a recent trip to a Wisconsin State Bar Solo Practice conference in Maryland, Madison criminal defense lawyer Stephen Meyer got a glimpse of the courtroom of the future.

During a mock trial demonstration, the criminal defense lawyer from Madison and his colleagues were shown a 3D hologram of an intestinal blockage that was part of the case. A juror could walk through that hologram.

“We experience life in 3D but watch it in 2D,” he said. “There’s lots of interesting stuff going on.”

That Maryland courtroom is a far cry from the courtroom that Meyer started out in more than 30 years ago. In his experience, he said, the use of PowerPoint or another equivalent during opening and closing statements is now standard.

“When I started, it didn’t exist,” he said. “Computers didn’t exist.”

And the possibilities are growing.

Bob Gramann, president of Gramann Reporting Ltd., which provides litigation services, said one increasingly used bit of technology allows attorneys to attend depositions, get real-time feeds from court reporters, view and mark documents, and hear testimony – all remotely. He said the systems are now more common on the coasts but will come to Milwaukee and the rest of the Midwest soon enough.

In terms of presentation, applications such as TrialPad and TranscriptPad are making tablets indispensable during trials, said Gramann. Both allow attorneys to present prerecorded video depositions and documents and make notations.

“It’s ubiquitous,” he said. “You can get everything on anything.”

Personal injury lawyer Ann Jacobs said it is astonishing h0w inexpensive technology has become. Technology that used to be reserved for big trials is now available for even small fender-bender cases, she said.

However, Jacobs points out that new technology could put some lawyers at a disadvantage during a trial.

“If used poorly,” she said, “juries notice. You really do need to be competent in the use of technology in trials.”

— Erika Strebel

Legal News

- FBI launches criminal investigation into Key Bridge collapse

- Man charged in slaying after woman’s leg found at Milwaukee-area park

- Minnesota man guilty in fatal stabbing of teen on Wisconsin river, jury finds

- Wisconsin teen sentenced in bonfire explosion that burned at least 17

- Wisconsin man who broke into home, ate victim’s chicken, slept in victim’s bed, receives prison and jail sentences

- Judge refuses to dismiss Hunter Biden’s gun case

- House passes reauthorization of key US surveillance program after days of upheaval over changes

- Milwaukee Police officer traveling to Georgia training retires before facing discipline

- Evers to ask legislature to approve largest increase in state support for UW System in two decades

- 7th Circuit Court of Appeals proposes new rules

- Federal agencies allege toxic work environment for women in new report

- Wisconsin man sentenced for sex trafficking a woman and a minor online

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula