Lack of lawyers in Wisconsin ‘legal deserts’ impedes justice

By: Michaela Paukner, [email protected]//November 3, 2020//

Lack of lawyers in Wisconsin ‘legal deserts’ impedes justice

By: Michaela Paukner, [email protected]//November 3, 2020//

Although Attorney Debra DeLeers’ office is just outside of Green Bay, that’s not always where she finds her clients.

Although Attorney Debra DeLeers’ office is just outside of Green Bay, that’s not always where she finds her clients.

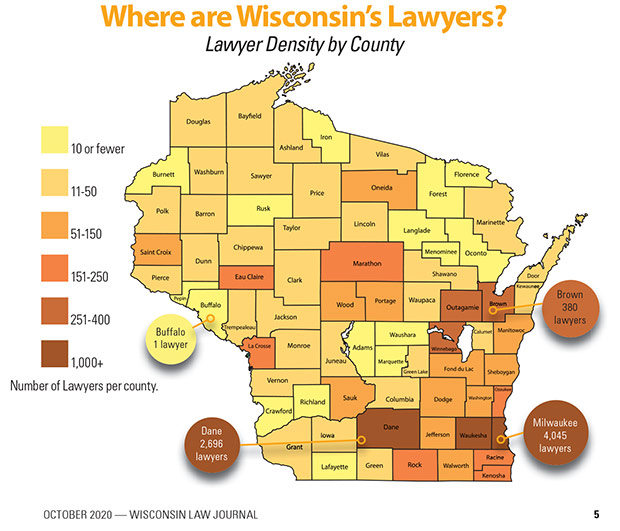

“My practice area — from a demographic outlay — is generally Brown County, Oconto County, Door County and Kewaunee County,” DeLeers said. “In those outlying areas, there’s really not a lot of predominant firms.”

DeLeers primarily practices estate planning and elder law at her firm, DeLeers Legal, in De Pere. It’s not far from where she grew up, near Luxemburg, a small town east of Green Bay in Kewaunee County. That’s part of the reason why she chose to serve clients in surrounding rural areas.

“I’m very much someone who is proud of my roots and where I come from,” DeLeers said. “It’s very rewarding to work in those areas because people do look to you for guidance as they’re navigating some of these legal junctures, and you really get to build some fantastic relationships.”

Brown, Door, Kewaunee and Oconto counties have 438 attorneys in total — most of whom work in the city of Green Bay. DeLeers said many residents in the surrounding counties look to Green Bay for legal services — especially when they’re seeking an attorney with a particular specialty. She said the city has a wealth of legal resources and upstanding, well-recognized firms. The same, unfortunately, cannot be said for nearby, rural areas.

“In the area as a whole, it would be extremely beneficial to have more attorneys who are targeting some of the rural areas, who are making a concerted effort to meet with those individuals or let those individuals know we’re here,” DeLeers said.

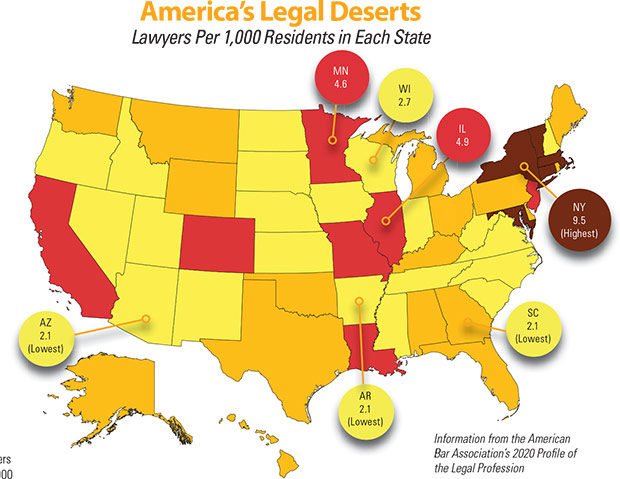

The American Bar Association considers those rural counties legal deserts — places with few or no lawyers. Its “2020 Profile of the Legal Profession” assessed the number of lawyers for each 1,000 residents of each state to show where legal services are hard to come by or even don’t exist.

Identifying Wisconsin’s legal deserts

There are roughly four lawyers for every 1,000 U.S. citizens, according to the ABA report. That may seem like a lot, but the more than 1.3 million attorneys in the U.S. aren’t dispersed equally. Big cities tend to attract more lawyers, resulting in high concentrations of legal services in some areas. Other places remain deserts.

Wisconsin has an average of 2.7 lawyers for every 1,000 residents — much fewer than both New York, which has the highest national average of 9.5 lawyers for every 1,000 residents, and Minnesota, which has 4.6 lawyers for every 1,000 residents. Within Wisconsin, attorneys are concentrated in and around the largest cities, leaving rural places short of legal services.

The Access to Justice Commission, set up by the Wisconsin Supreme Court in 2009, works to bring legal aid to low-income and rural residents. The commission sponsors Wisconsin Free Legal Answers, an online legal clinic, to provide this sort of help to people living in rural places.

Jeff Brown, pro bono program manager at the State Bar of Wisconsin, works for the commission in a role similar to an executive director. He said more than half of people using Wisconsin Free Legal Answers are rural residents.

“It’s not uncommon to have a situation where someone in, say, Barron County has a question, and the volunteer responding to the question is a lawyer in Madison and Milwaukee, where lawyers are concentrated,” Brown said.

Nearly two-thirds of all Wisconsin lawyers work in Dane, Milwaukee and Waukesha counties. Even in those places, people with low incomes have a hard time making use of legal services. Brown said a lack of state funding prevents legal-aid offices from doing all they could do.

“Most have to turn away more clients than they can serve,” Brown said. “They have to constantly scramble to assemble new pieces of funding to bring on lawyers to handle emerging issues like what we’re experiencing now with housing issues and soon bankruptcy issues and employment issues.”

Wisconsin’s 2019-21 state budget allocates $500,000 a year for civil services to low-income families, in addition to federal and private funding. In contrast, Brown noted, Minnesota provides $12 million and Michigan $5 to $6 million for such services.

“It’s a strange situation,” Brown said. “I can’t describe it exclusively to the politics of Wisconsin because there are ‘red states’ that have huge amounts of funding for civil legal aid like Texas. For whatever reason, there just has been a comparative underinvestment over a long period of time.”

Since its beginnings, the commission has been involved in state budgets, having a goal of spending more on civil legal services. Brown said the commission has received bipartisan support and has made some progress, but its work will continue in the next budget.

“In the same way that they came together to raise the private bar rate to help stabilize the indigent defense system, I think that’s the same sort of approach that we’re going to need if we’re going to raise the bar for how we support our civil legal aid providers in Wisconsin,” Brown said.

Finding solutions

The Access to Justice Commission has discussed various ways to provide legal services to more people in rural Wisconsin. The commission advocates for using technology to connect people with legal services and the courts virtually, while also considering what’s needed to bring in-person services to rural areas.

Brown said the State Bar has tried to encourage lawyers to set up rural practices, connecting them with mentors and resources needed for success. The commission has also considered adopting strategies other states are using to establish legal oases amid legal deserts — such as South Dakota’s Project Rural Practice.

The State Bar of South Dakota worked with the state legislature to provide incentive payments to attorneys who open up practices in qualified rural counties. The payments equal 90% of one year’s tuition and fees at the University of South Dakota School of Law.

Patrick Goetzinger, the former South Dakota State Bar president who helped set up Project Rural Practice, discussed some of the program’s successes during a virtual ABA presentation about legal deserts in the U.S. He said the decision to set up a rural practice proves to be a good career step for young lawyers.

“These young lawyers are getting cases of substance, files of substance, and are experiencing opportunities in the practice probably earlier than they would have experienced had they gone to an urban law firm,” Goetzinger said.

The participating attorneys also often become community leaders, helping to improve more than just access to justice in small towns.

“The communities know how important it is to have a lawyer on Main Street driving individuals onto Main Street,” Goetzinger said. “Those young lawyers who are participating in that role are magnets for economic development.”

DeLeers has seen the same effect in Wisconsin.

“In smaller communities, when you come in with your credentials and hang your shingle, you are viewed as one of the movers and shakers in the community,” DeLeers said. “There’s a lot of opportunity to get involved and really step into that leadership role.”

She encourages attorneys to make connections in places they intend to work and find a mentor, especially if they’re new to the practice.

“If you have that mentorship and that support system from a practice standpoint, I think it could be an extremely rewarding and lucrative career because you are working in an area that needs an attorney,” DeLeers said.

Legal News

- Outside the RNC, small Milwaukee businesses and their regulars tried to salvage a sluggish week

- Biden called to resign immediately after the president announces he won’t seek reelection

- Biden drops out of 2024 presidential race, endorses Harris

- Local PA cops allegedly thought Trump’s would-be assassin was Secret Service

- Biden-Lead Secret Service admits agency denied past requests by Trump’s campaign for tighter security

- Class action filed against Walgreens

- Former Waukesha County Sheriff’s Office lieutenant pleads guilty to smuggling contraband

- Two dead, one injured after Ozaukee County water rescue

- RNC Final Day: Trump accepts GOP Nomination

- Wisconsin officials intervene in Planned Parenthood action

- 7th Circuit adopts modifications to Rules 31, 34, 40, 47 and 60

- MPD issues statement on outside agency officer assignments

Case Digests

- Ineffective Assistance of Counsel; Double Jeopardy; Sentencing

- Ineffective Assistance of Counsel; Sexual Assault-Prosecutorial Misconduct

- Contract-Negligence

- Criminal Law; Juvenile Law; Discovery

- Family Law; Child Support; Property Division First paragraph(s)

- Ineffective Assistance of Counsel- Exclusion of Evidence of Witness Bias

- Postconviction Relief-Sentencing-Ineffective Assistance of Counsel

- 14th Amendment – Due Process

- Criminal-Sentencing Guidelines – Enhancement

- Bankruptcy-Tax

- Civil Rights – 14th Amendment-Jury Instructions

- Contract; Foreclosure and Property