CRITIC’S CORNER: Convicting Avery (and overturning Denny)

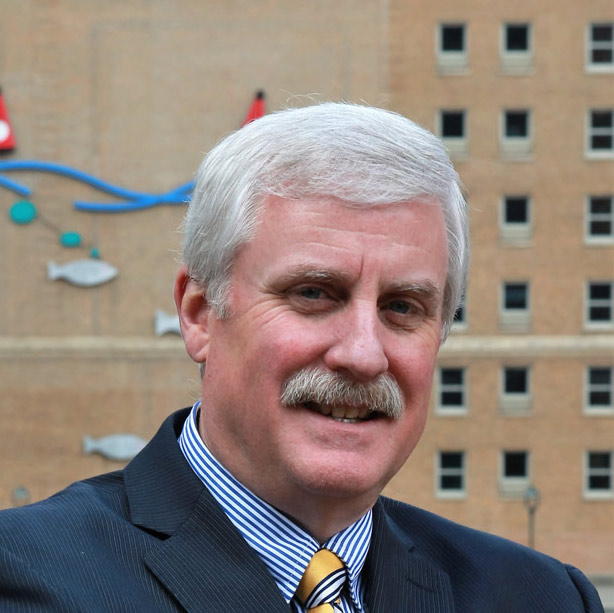

By: Michael D. Cicchini//June 6, 2016//

The wildly popular Netflix documentary “Making a Murderer” chronicles the two convictions of Steven Avery. The bulk of the documentary concentrated on Avery’s second case — his trial for the murder of Teresa Halbach — in which there was a great deal of evidence that someone else, other than Avery, committed the crime.

Yet, as the defense attorney Jerry Buting lamented in the documentary, the judge used Wisconsin’s so-called Denny rule (State v. Denny, 120 Wis. 2d 614 (Ct. App. 1984)) to prevent the defense from arguing that a specific third party, other than Avery and his codefendant, had killed Halbach. Sure, the defense team was free to contend that Avery wasn’t responsible for the crime, but they were prevented from telling the jury who they thought had committed it.

The Denny rule is a bizarre double standard that often operates to shut down third-party defenses that might be brought by defendants. It does this by placing a much higher evidentiary burden on defendants than on the state.

For example, in order to use a third-party defense at trial, a defendant must first prove there is “a direct connection” between the third party and the crime. Yet when it comes to the prosecutor’s case, the jury will be instructed that circumstantial evidence “is not necessarily better or worse than direct evidence.”

Further, even when a defendant is able to provide direct evidence of a third party’s guilt, Denny still shuts down the defense. How? By also requiring the defendant to prove the third party’s motive for the crime. Here then comes yet another double standard, since the jury will be instructed that “the state is not required to prove motive on the part of a defendant in order to convict.”

Denny is an irrational, truth-suppressing rule that Avery’s trial and appellate judges used to foreclose his third-party defense in the Halbach murder case. Even worse, the application of Denny to Avery’s first case not only resulted in a wrongful conviction but also allowed a rapist (Gregory Allen) to roam free.

About 20 years before the Halbach case, Avery was tried and convicted for the rape of Penny Beerntsen. Ten years later, Avery was citing newly discovered evidence as the basis for an appeal. Because of advances in DNA testing, Avery was able to prove that the scrapings from underneath Beerntsen’s fingernails contained DNA that did not belong to her or Avery. What’s more, Avery provided evidence that law enforcement had actually identified and investigated another suspect, but failed to disclose these endeavors to Avery’s trial lawyer.

This new evidence of third-party guilt, Avery contended, should be considered along with his 16 alibi witnesses and Beerntsen’s initial description of the perpetrator — a description that did not match Avery’s appearance. Therefore, Avery argued, he should get a new trial.

The court, however, relied in part on Denny to deny Avery’s appeal. Despite the main reasons for doubting his conviction, it wasn’t enough that Avery could point to another suspect and also demonstrate that DNA from the victim did not belong to her or Avery. Such evidence pointing to a third-party’s guilt, the court held, was far too speculative. At best, it provided “a possible ground of suspicion against another person” and would not be admissible under Denny. Therefore, the court affirmed the conviction and Avery remained incarcerated.

Avery was eventually freed, but not until a decade or so later, when new DNA testing conclusively proved that biological samples from the victim belonged to Allen. During that intervening time, Allen had remained free and had committed at least two more sex crimes, including another violent rape.

The lesson in all of this is that law enforcement may suffer from subconscious tunnel vision, may do a poor job investigating a crime, may intentionally target an innocent person, or may simply be overworked. And when courts handcuff defendants with law enforcement’s deficiencies and limitations, guilty people will slide under the radar.

In other words, even if courts don’t care about convicting innocent people, they need to remember the other half of this equation: When courts use Denny’s irrational double standard to suppress evidence of third-party guilt, guilty third parties will go free. Law enforcement’s flaws are deep and many, and we all lose when Denny prohibits defendants from doing the job that law enforcement should have done but failed to do. Until Denny is overturned, we’ll never know how many Gregory Allens are roaming free and committing more crimes in Wisconsin.

For more on the absurdity of the Denny rule, see my article, “An Alternative to the Wrong-Person Defense,” which is available on the articles page of CicchiniLaw.com. And for more on the Steven Avery and Brendan Dassey convictions, stay tuned for my forthcoming book, “Convicting Avery: The Bizarre Laws and Broken System behind ‘Making a Murderer,’” to be published by Prometheus Books early in 2017.

Legal News

- Wisconsin attorney loses law license, ordered to pay $16K fine

- Former Wisconsin police officer charged with 5 bestiality felony counts

- Judge reject’s Trump’s bid for a new trial in $83.3 million E. Jean Carroll defamation case

- Dozens of deaths reveal risks of injecting sedatives into people restrained by police

- The Latest: Supreme Court arguments conclude in Trump immunity case

- Net neutrality restored as FCC votes to regulate internet providers

- Wisconsin Attorney General asks Congress to expand reproductive health services

- Attorney General Kaul releases update at three-year anniversary of clergy and faith leader abuse initiative

- State Bar leaders remain deeply divided over special purpose trust

- Former Wisconsin college chancellor fired over porn career is fighting to keep his faculty post

- Pecker says he pledged to be Trump campaign’s ‘eyes and ears’ during 2016 race

- A conservative quest to limit diversity programs gains momentum in states

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula