For Colleen Meloy, success in the courtroom is both nature and nurture.

For Colleen Meloy, success in the courtroom is both nature and nurture.

Like her father and grandfather, Gary and Don Meloy, respectively, she is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin Law School. So to some degree, law is in her blood.

But she also has been the beneficiary of phenomenal mentoring, she said.

Her good fortune began when she was hired as a 2L law clerk and occasionally assisted Madison lawyer Barrett Corneille with his medical-malpractice defense cases. A few years later, after Corneille had started a boutique civil-litigation defense law firm, Meloy was helping him with a med mal case when she asked, “Can I do just this?”

To her happy surprise, he said yes.

A partnership was born, with Corneille as lead counsel and Meloy second-chairing him. All of their cases involve complex science, damages alleged in the multi-millions, and clients potentially losing their professional reputations.

The stress occasionally is off the charts, Meloy said, but she cannot think of a better focus for her career.

“I think I love medicine even more than I love the law. Maybe I didn’t choose the right path,” she said with a laugh. “Being in medical negligence, I’m able to learn different medicine with every case. That keeps it interesting.”

She also enjoys her work with physicians and nurses.

“They’ve gone into their careers to help people,” Meloy said. “They’ve had a bad outcome with a patient. They’re devastated by that. And now they have to face litigation.”

She and Corneille have proven themselves a winning team for their clients.

Consider, for example, a 2008 no-negligence jury verdict they obtained for a maternal fetal medicine specialist after a two-week trial in Dane County. Plaintiffs argued that delays during delivery cause the child’s cerebral palsy.

The defense successfully moved the court for blood testing in addition to an IME. Those blood-test results were critical to their client’s persuasive causation defense. Meloy said she considers the case a career highlight.

Her colleague, Gina Meierbachtol, said Meloy has certain strengths in the courtroom that complement the work of Corneille.

“Colleen’s great at preparing witnesses,” Meierbachtol, who counts Meloy as her principal mentor, said. “She’s incredibly detail oriented and organized. She’s got more charts than anyone I’ve ever seen.

“And she’s very comfortable and confident in what she does.”

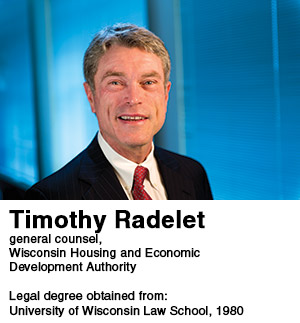

Meticulous attention to detail drew Timothy Radelet into law and, in a couple of ways, into state procedure.

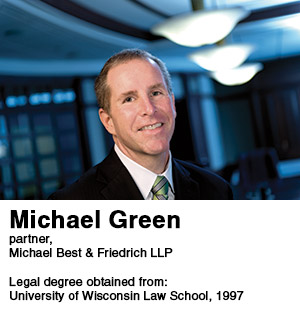

Meticulous attention to detail drew Timothy Radelet into law and, in a couple of ways, into state procedure. Michael Green’s legal work underpins a very public development underway in Madison: redevelopment of The Edgewater Hotel.

Michael Green’s legal work underpins a very public development underway in Madison: redevelopment of The Edgewater Hotel. When Vicki Margolis left private practice in 2007, she found the grass wasn’t immediately greener.

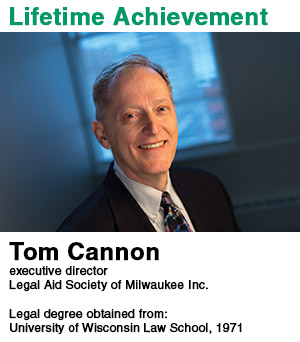

When Vicki Margolis left private practice in 2007, she found the grass wasn’t immediately greener. Tom Cannon chooses his words carefully.

Tom Cannon chooses his words carefully. When Debra Tuttle became the chief mediator for the Milwaukee Foreclosure Mediation Program, she didn’t see a long future ahead.

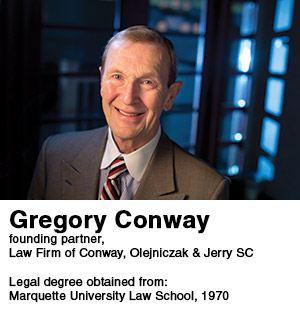

When Debra Tuttle became the chief mediator for the Milwaukee Foreclosure Mediation Program, she didn’t see a long future ahead. Green Bay attorney Gregory Conway credits his family legal pedigree for an extra edge in the confidence department.

Green Bay attorney Gregory Conway credits his family legal pedigree for an extra edge in the confidence department. On the wall behind John Ebbott’s desk is a picture of him and Martin Luther King Jr., taken when the iconic figure was in Madison in the 1960s.

On the wall behind John Ebbott’s desk is a picture of him and Martin Luther King Jr., taken when the iconic figure was in Madison in the 1960s. Bringing a former Wisconsin Supreme Court justice onto the team at Gonzalez Saggio & Harlan LLP was not a universally popular idea.

Bringing a former Wisconsin Supreme Court justice onto the team at Gonzalez Saggio & Harlan LLP was not a universally popular idea. Christopher Krimmer said he grew up introverted and shy, with low self-esteem.

Christopher Krimmer said he grew up introverted and shy, with low self-esteem. Randal Brotherhood takes his work wherever he goes.

Randal Brotherhood takes his work wherever he goes. A litigator for the past 46 years, Bruce O’Neill shows no sign of slowing down.

A litigator for the past 46 years, Bruce O’Neill shows no sign of slowing down.