A slow fade: Problems arise as lawyers drop from the Legislature

By: Amy Karon, [email protected]//June 18, 2012//

A slow fade: Problems arise as lawyers drop from the Legislature

By: Amy Karon, [email protected]//June 18, 2012//

Robert Kovach, chief of staff for state Sen. Frank Lasee, falls silent to consider the consequences of confusing wording in a major new landlord-tenant law.

Finally, in one short sentence, Kovach predicts a possible outcome and unintentionally summarizes what some consider the result of fewer attorneys serving in the Legislature.

“We’re going to have to see what the judges say,” Kovach said.

The bill, which Lasee, R-De Pere, introduced in February and Gov. Scott Walker signed five weeks later, was designed to standardize existing statutes, easing burdens for residential landlords and helping prevent conflicts with renters.

But the law requires both landlords and tenants fill out check-in sheets. It is silent on what to do if they disagree about a property’s condition.

Concerns about that type of silence do not just apply to the landlord-tenant law.

State Sen. Glenn Grothman, R-West Bend, voted for the law. But Grothman, who is one of just two Republican senators who are lawyers, also has dealt with approved legislation that he said had holes.

“People who aren’t attorneys,” he said, “sometimes pass laws without realizing the full burden that they impose on people because of legal ambiguities.”

Grothman, a retired attorney with 10 years of experience in estate planning and real estate tax, focused on 2009 Wisconsin Act 20, which provided for as much as $300,000 in compensatory and punitive damages for employees found to have been victims of workplace discrimination. A Wisconsin State Bar analysis found no known cases in which an employee alleging discrimination was awarded such damages under Act 20 but noted the act could have influenced settlements.

“I felt that was a horrible law because of the burdens it imposes on employers even if they are innocent,” said Grothman, who helped repeal Act 20 during the last legislative session. “I think thinking like a lawyer helped me reach that conclusion.”

But the dwindling number of legislators who think like lawyers has raised concerns there is insufficient input from people who understand how laws play out in real life and can prevent unintended consequences that end up being litigated in court.

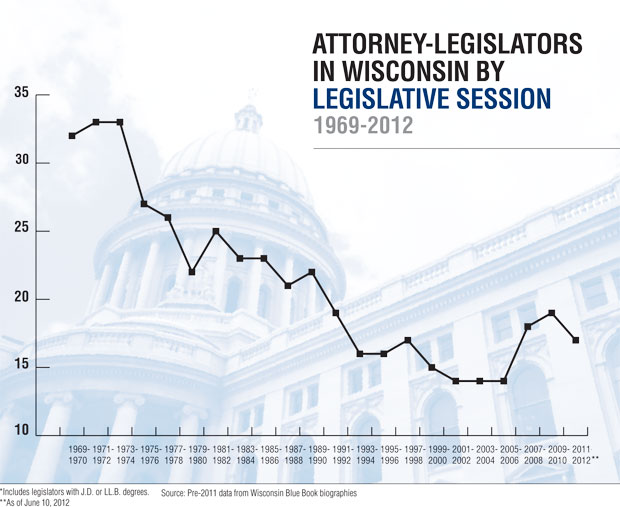

In fact, the number of Wisconsin state senators and representatives who are attorneys has declined markedly during the past four decades. In 1969, 32 of Wisconsin’s 132 legislators were attorneys. Now, 17 are.

When voters first elected Sen. Fred Risser, D-Madison, to the Senate in 1962, almost half his 32 colleagues were fellow lawyers. Now he’s one of five.

“When I started out, this was a part-time job,” said Risser, 85, who has served 55 years in the Legislature. “You served two or three months a year, twice a year. Then you’d go back home and practice law for a year and a half.

“Not just lawyers are gone. Farmers are gone. Teachers are gone. More than half of us (in Wisconsin) are full-time legislators now.”

That downward trend of attorney-legislators, which plateaued in Wisconsin in the early 1990s, isn’t unique to the state.

In 1976, lawyers were the most commonly represented profession in U.S. statehouses, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. But by 2007, full-time legislators had surpassed attorney-legislators, and their numbers had fallen to about 15 percent. The rate in Wisconsin today is slightly lower.

View this data as a spreadsheet (XLS)

A slew of obstacles stand between most lawyers and capitol chambers. Among those, financial hurdles rank high.

In 2007, attorneys in other areas of government reported a median pre-tax income of $82,000, and those in private practice made $100,000, according to the Wisconsin State Bar’s most recent survey of its members.

State Sen. Lena Taylor, D-Milwaukee, said her $49,000 annual salary couldn’t match that, especially when considering newly minted lawyers’ soaring debt loads.

During 2010-11, about three-quarters of University of Wisconsin-Madison law students graduated with debt, said Susan Fischer, UW-Madison’s director of financial aid. Law graduates with debt averaged almost $100,000 in loans, and about $67,000 of that was from law school tuition and living expenses.

And while Risser, like Taylor, still practices law part-time, he said the responsibilities of modern-day lawmaking — committee work, special sessions and increased communication with constituents — have made it almost impossible for many attorneys to do so.

That doesn’t mean the Capitol is short on lawyers. Nonpartisan legislative service agencies, such as the Legislative Council and the Legislative Reference Bureau, conduct research for individual legislators and committees, help draft bills and serve as advisors. So do lawyer-lobbyists, including three from the Wisconsin State Bar.

“Is [the decline of lawyer-legislators] a problem? The simple answer is no,” said Robert Fassbender, a veteran lobbyist with Hamilton Consulting Group who also has 10 years of experience in environmental law. “The best attributes of legislators are good common sense and well-rounded life experiences. They are the quintessential generalists.

“Lawyers traditionally are advisors. What we really need are lawyers in advisory roles in the Legislature or at agencies. Some committees warrant not only a committee staffer but a committee counsel.”

But others on both sides of the aisle said legislators with legal training, especially those who practiced law, serve critical functions because they could review a bill’s wording and envision its implications to negotiations and court cases.

“Many of these issues are incredibly complex, and what appear to be minor changes in the law can have major consequences,” said Joseph Strohl, a lobbyist and former Democratic state senator who is not an attorney. “It’s very difficult explaining those intricacies of the law to legislators who themselves are not lawyers.”

But attention to such details could have prevented problems with the landlord-tenant law, said state Rep. Anthony Staskunas, D-West Allis, one of three attorney-legislators who have announced plans to retire at the end of this session.

Staskunas practices landlord-tenant law. He said the law was amended and passed in a rush without enough feedback from attorneys.

The result, he said, is not only the confusion around the check-in sheet, but the fact that the law applies to commercial leases when that wasn’t the intention.

But Kovach, who is not an attorney, defended the law. He said several attorneys from the legal counsel department reviewed the legislation, and Lasee’s office still is working with the Wisconsin Builders Association and several apartment associations to clarify the law.

“We had attorneys from the Wisconsin Builders Association looking at it from day one,” Kovach said. “We thought we were pretty clear in the bill language.

“What was entered into statute may be harder to make clear.”

View this data as a spreadsheet (XLS)

State Bar: No plans to change lobby level

When Republican state legislators introduced last year’s controversial tort reform bill, two attorney organizations reacted as might be expected.

The Wisconsin Defense Counsel supported the legislation, while trial lawyers with the Wisconsin Association for Justice opposed the proposal.

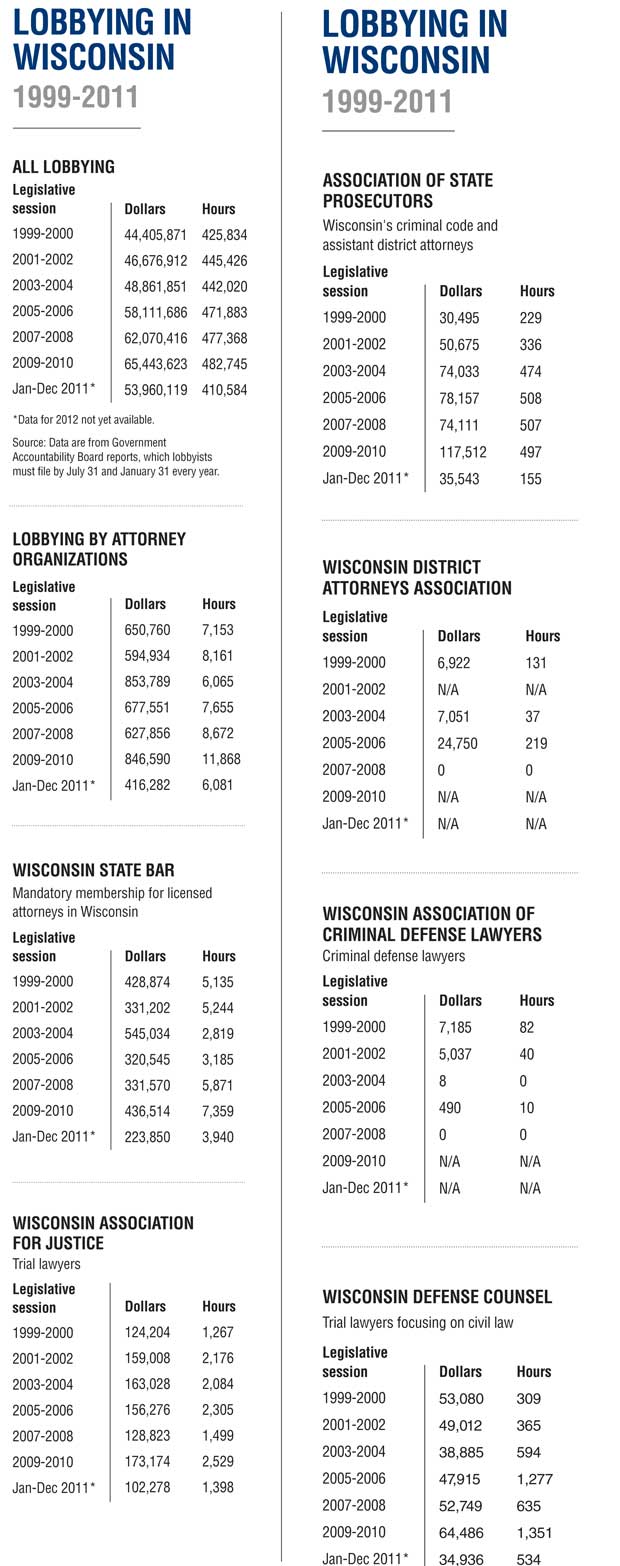

But the Wisconsin State Bar, which spends more money on lobbying than any other attorney group in the state, remained absent from the mix.

That response isn’t out of character for the bar, said Ray Carey, a lawyer-lobbyist with Foley & Lardner LLP and former director of the Wisconsin Assembly Republican Caucus.

“The bar is split in a hundred different directions,” Carey said. “The most obvious split is between the plaintiffs’ bar and the defendants’ bar.

“It’s tough for them to get involved in the hyper-partisan, contentious issues that make headlines because their members tend to be on opposite sides of those issues.”

The State Bar’s 10 lobbying sections did take positions on about 40 bills during the 2011-12 legislative session, according to data from the bar’s website. But the sections, which independently operate from the bar’s Board of Governors, prevailed in less than half those cases.

One possible reason: Although Wisconsin lobbying organizations spent $21 million more in 2009-10 compared with a decade earlier, the State Bar’s expenditures substantially did not change during that period, according to Government Accountability Board data.

On average, the bar spends about $400,000 on lobbying per legislative session, less than 4 percent of its annual budget. That’s more than twice the money spent in 2009-10 by the state’s second-largest attorney group, the Wisconsin Association for Justice, but only about one-sixth that of the top-ranking spender, the Wisconsin Education Association Council.

What’s more, the bar’s lobbying reports to the GAB suggest the organization spreads its efforts thinly. During the past two legislative sessions, bar lobbyists reported devoting almost 100 percent of their time to what the GAB calls “minor effort,” or issues that individually account for less than 10 percent of an organization’s overall lobbying expenditures.

State Bar officials declined requests to interview the organization’s lobbyists, citing their busy schedules.

Public Affairs Director Lisa Roys said the bar’s leaders don’t plan to increase or cut back on lobbying activities.

Despite the state’s lack of attorney-legislators, the State Bar does not actively encourage attorneys to run for office, she added, in part because the organization is prohibited by law from endorsing candidates.

In 2001, George Brown, the bar’s executive director, published two articles in Wisconsin Lawyer urging attorneys to join the Lawyers Legislative Action Network, a “grassroots” program that, according to the State Bar website, would give “attorneys an organized legislative lobbying effort.”

The program, according to Brown’s articles, especially was important in light of how few attorneys served in the Legislature.

But Roys said the network now was defunct. News releases, Facebook posts and tweets issued by the network’s replacement, the Rotunda Report, reveal a mix of general announcements and analyses of proposed legislation, but no calls to action.

Gov. Scott Walker signed the tort reform bill in January 2011.

Although the bar’s Board of Governors opposed some of provisions, section attorneys never took a position, saying they had inadequate time to study the issues at stake, according to an analysis on the bar’s website.

Legal News

- Attorney General Kaul releases update at three-year anniversary of clergy and faith leader abuse initiative

- State Bar leaders remain deeply divided over special purpose trust

- Former Wisconsin college chancellor fired over porn career is fighting to keep his faculty post

- Pecker says he pledged to be Trump campaign’s ‘eyes and ears’ during 2016 race

- A conservative quest to limit diversity programs gains momentum in states

- Wisconsin prison inmate pleads not guilty to killing cellmate

- Waukesha man sentenced to 30 years for Sex Trafficking

- 12-year-old shot in Milwaukee Wednesday with ‘serious injuries’

- Milwaukee man convicted of laundering proceeds of business email compromise fraud schemes

- Giuliani, Meadows among 18 indicted in Arizona fake electors case

- Some State Bar diversity participants walk away from program

- Wisconsin court issues arrest warrant ‘in error’ for Minocqua Brewing owner

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula