Pro se representation comes at a cost

By: GREGG HERMAN//November 15, 2022//

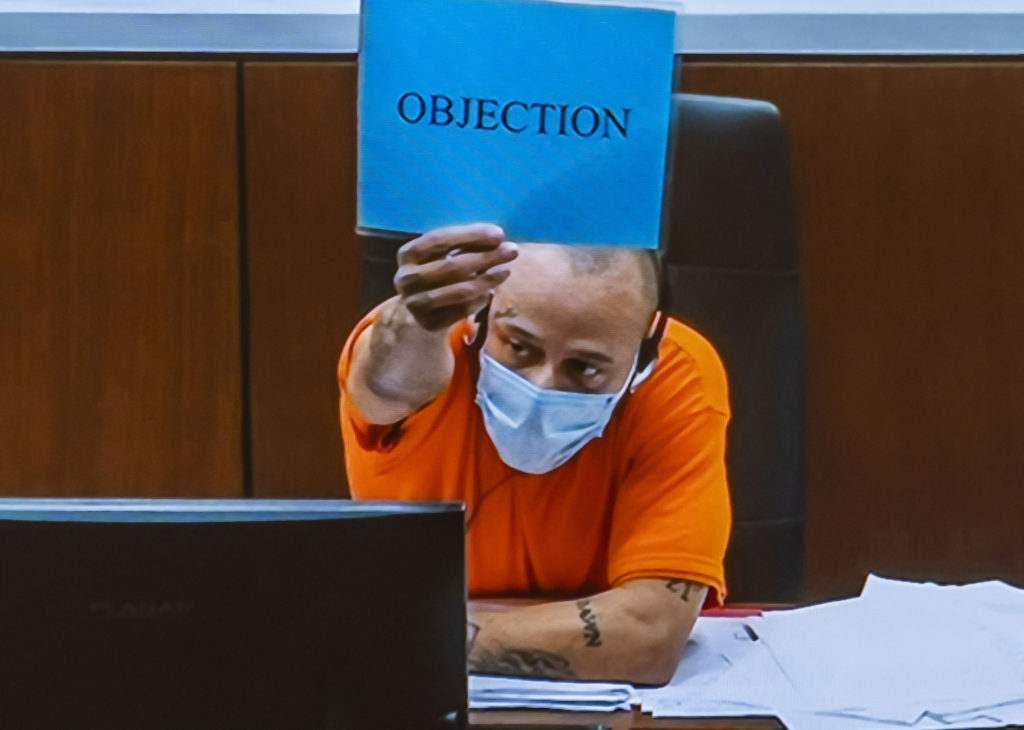

Few recent trials have attracted as much attention in the non-legal world than the Brooks trial in Waukesha.

Most of the comments relate to either praising the patience of Judge Dorow (much deserved) or criticizing the legal system for allowing such a circus to occur in the first place. The answer to the latter, as discussed in a previous column, is the constitutional right of a criminal defendant for self-representation.

The result, as anticipated, is that Mr. Brooks was convicted and will be sentenced to serve more years than he can possibly live.

Outside of the occasional story when appellate courts affirm the conviction, he will rot in prison while the victims and their families have to find the means to cope with the aftermath.

Still, given the attention devoted to the defendant representing himself, it seems to warrant one more column to describe my experience as a prosecutor with a pro se defendant in a felony trial.

The defendant had a long, long prior record, but they were all for minor, non-violent convictions, such as theft, burglary, more thefts and even more thefts. The case I handled involved his breaking into a building, perhaps looking for food. Typically, such a case would be easily resolved, but the defendant would not plead to anything and given his prior record, I would not dismiss it.

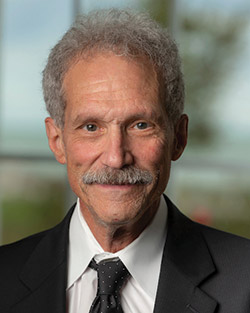

When he insisted on representing himself, he agreed to standby counsel. The trial judge appointed Fred Kessler, who had resigned from the bench a few months prior to run unsuccessfully for Congress.

During voir dire, the judge asked the typical question about whether any of the potential jurors had any knowledge of the prosecutor, the defendant, any of the witnesses or the standby counsel. None did. At a break, Judge Kessler said to me: “I just spent thousands and thousands of dollars on television to run for Congress. Don’t you think at least one of them might have heard of me?”

I’m certain that Judge Kessler was more upset by that than he was about the eventual verdict.

Speaking of which, of course the jury found the defendant guilty. Sentencing was easy: He had been in jail waiting for trial for longer than any reasonable sentence, so the judge sentenced him to time served. When the judge told him that he could return to the jail for his personal items, he responded that he had none. He was simply free to go.

As we left the courtroom together with the lead detective, the defendant asked Judge Kessler for a few dollars to buy dinner and a ticket out of town. As Judge Kessler opened his wallet, he asked if the detective and I would join him. We both did so, as it was the right thing to do. We all agreed that it was undoubtedly the first time in history that the prosecutor and the lead detective gave money to a defendant after he had been convicted of a felony. Or any other time.

The take away? Only one: Strange things happen in our court system!

Legal News

- State Bar leaders remain deeply divided over special purpose trust

- Former Wisconsin college chancellor fired over porn career is fighting to keep his faculty post

- Pecker says he pledged to be Trump campaign’s ‘eyes and ears’ during 2016 race

- A conservative quest to limit diversity programs gains momentum in states

- Wisconsin prison inmate pleads not guilty to killing cellmate

- Waukesha man sentenced to 30 years for Sex Trafficking

- 12-year-old shot in Milwaukee Wednesday with ‘serious injuries’

- Milwaukee man convicted of laundering proceeds of business email compromise fraud schemes

- Giuliani, Meadows among 18 indicted in Arizona fake electors case

- Some State Bar diversity participants walk away from program

- Wisconsin court issues arrest warrant ‘in error’ for Minocqua Brewing owner

- Iranian nationals charged cyber campaign targeting U.S. Companies

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula