CRITIC’S CORNER: Weird science in Wisconsin courts

By: Michael D. Cicchini//January 31, 2017//

Steven Avery was convicted of murder in 2007. At his trial, the state called numerous scientific experts to help seal his fate. Then, a few years later, Wisconsin adopted the stricter Daubert standard for the admissibility of expert testimony. Had this supposedly tougher standard been in effect earlier, how would it have affected Avery’s trial?

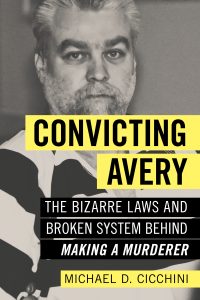

Below is an excerpt from chapter 4 (Weird Science) of my forthcoming book, “Convicting Avery: The Bizarre Laws and Broken System behind Making a Murderer” (Prometheus Books, April 4, 2017). The excerpt is reprinted with permission from the publisher (footnotes have been renumbered):

… In theory, there is a legal explanation for how the state was able to pass junk science off as science in Avery’s case. In Wisconsin during that time, there was an incredibly lax standard for the state’s use of expert testimony. … And this lax standard posed a significant problem: the state was always able to use a so-called expert to paint the face of credibility on a garbage case. And even when the defense was able to effectively cross-examine the state’s expert, this would only be meaningful if the jury was interested in, and capable of understanding, nuanced topics such as scientific testing protocols and method detection limits. In many instances, even assuming the jurors had not prejudged the defendant, they simply didn’t care about or understand the scientific concepts being debated at trial. In the end, all they really heard was the government’s so-called expert concluding that the defendant was guilty.

Since Avery’s trial, however, Wisconsin has moved to the nationally recognized Daubert standard for the admissibility of expert testimony. [1] This standard, in theory, is tougher to satisfy. …

However, like many of the legal standards in criminal law, this one is factor-laden and can be twisted and turned as easily as the bookcase in Avery’s bedroom (see chapter 3 [Seek, and (Eventually) Ye Shall Find]). When determining whether the testimony “is the product of reliable principles and methods,” courts can pick and choose from among ten or more factors. …

As soon as Wisconsin announced the change to the Daubert standard for the admissibly of expert testimony, I predicted aloud, to anyone who would listen, that even under this supposedly tougher standard, courts would continue to allow the state to call any so-called expert it wished for any purpose whatsoever. And that is exactly what has happened: “In theory, Wisconsin’s new test for the admissibility of expert testimony is flexible but has teeth. In practice, it’s flexible and has dentures. Literally every Daubert challenge litigated on appeal since [the new law] became effective has failed.”[2]

As a result, jury trials have been indistinguishable from those in the pre-Daubert, anything-goes era of expert testimony. In one Wisconsin case, the appellate court allowed the state to use its expert even when the “expert testimony did not neatly fit the Daubert factors.”[3] The court’s reason: this type of testimony was commonly ruled admissible by “pre-Daubert Wisconsin courts.”[4]

That is rather curious reasoning. The legislature changed the law to take away the anything-goes standard and make it tougher to use so-called experts at trial. It would therefore seem that when the state’s proposed expert testimony does “not neatly fit the Daubert factors,” it should be excluded from evidence. And, when trying to find a way to admit such testimony under the new law, judges should probably not be allowed to rely on decisions from the “pre-Daubert Wisconsin courts,” as this, too, would seem to evade, rather than recognize, the new Daubert standard.

Given the Wisconsin appellate courts’ disdain for Daubert, it is likely that, even if Avery were tried today in the Daubert era, the trial court would still allow the state to use its weird, non-science science at trial. That is, the EDTA test (even without a known method detection limit), the testimony about the burn site (even though entirely speculative at best), and the DNA test (even with its contamination and the analyst’s disregard of testing protocol) may very well be deemed “the product of reliable principles and methods” under Daubert.

When there’s a will (and a handy, flexible, 10-factor test for the court to apply), there’s a way.

[1] Daniel D. Blinka, “The Daubert Standard in Wisconsin: A Primer,” Wisconsin Lawyer, March 2011.

[2] Wisconsin Public Defender, Admin., “Drug Recognition Evaluator Passes Daubert Test for Admissibility of Expert Testimony,” On Point, April 13, 2016.

[3] Wisconsin Public Defender, Admin., “Social Worker’s Testimony about Behavior of Child Abuse Victims Passes Daubert,” On Point, December 10, 2015.

[4] Ibid.

Legal News

- Milwaukee’s Common Council now has the most African Americans, women and openly LGBTQ members ever

- Office of School Safety Provides Behavioral and Threat Assessment Management Training Ahead of 25th Anniversary of Columbine Shooting

- Wisconsin Supreme Court to hear arguments in Democratic governor’s suit against GOP-led Legislature

- Lawsuit asks Wisconsin Supreme Court to strike down governor’s 400-year veto

- Wisconsin man pleads not guilty to neglect in disappearance of boy

- ACS Selects University of Wisconsin Law School’s Miriam Seifter for 2024 Ruth Bader Ginsburg Scholar Award

- People with disabilities sue in Wisconsin over lack of electronic absentee ballots

- Wisconsin Republicans ignore governor’s call to spend $125M to combat ‘forever chemicals’

- Native American voices are finally factoring into energy projects

- Steven Avery prosecutor Ken Kratz admits ‘mistakes were made’

- Colombian national extradited to Milwaukee faces International narcotics-trafficking conspiracy charge

- MPD: Milwaukee homicides down nearly 40 percent compared to last year

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula