Drug of choice: Milwaukee treatment court looking for long-term financing

By: Jack Zemlicka, [email protected]//July 28, 2011//

Drug of choice: Milwaukee treatment court looking for long-term financing

By: Jack Zemlicka, [email protected]//July 28, 2011//

Ten months ago Carlos Martinez had a choice.

Either enroll in Milwaukee County’s Drug Treatment Court program or head to prison, a place he had been 10 times during the past dozen years.

A habitual heroin and cocaine addict since age 16, Martinez, now 32, opted for the treatment program.

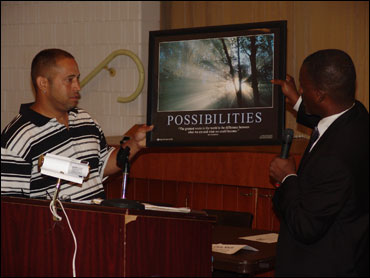

On July 27 he became the 30th graduate to complete the process launched in 2009.

The goal of the program is to provide a cost-effective and alternative solution to jail for a segment of nonviolent offenders facing a minimum of nine months behind bars.

“If I was not in the program,” Martinez said. “I’d be locked up.”

But absent long-term financing, offenders such as Martinez might not have that alternative to incarceration in the future.

In October 2012, two three-year federal grants that pay for Milwaukee’s Drug Treatment Program will expire and those who run the program are not sure where money will come from to sustain the program.

“We don’t have a definite plan,” said Larry Hopwood, Drug Treatment Court coordinator. “We’ve been submitting more grant applications.”

In June, Hopwood submitted a request for a three-year, $1 million federal grant to help sustain the program, primarily the part that evaluates and treats mental illness often associated with drug or alcohol addiction.

In the short term, Hopwood said the objective was to maintain the program through additional federal grants. He expected a response in October to a $1 million grant request.

But he acknowledged that it was hard to predict what money would be available once the dust settled in the federal budget battle.

“They are not funding as many of these as they were when we got ours,” he said.

Initially, the program received a $350,000 grant from the Bureau of Justice Assistance and $300,000 annually for three years from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Long term, Hopwood said state and county money, which largely has gone toward salaries for coordinators and support staff, could be an option through either sales tax revenue or other income tied to drug-related crimes.

Ideally, the program would be self-sustaining through money saved by not having people incarcerated in jail, said Milwaukee Circuit Court Judge Carl Ashley, who rotates out of drug court Aug. 1.

He and other supporters of the drug court system have discussed the potential for a Community Corrections Act, as implemented in other states, to help reallocate money spent on keeping people in jail, to providing better treatment options.

Ashley said a formal proposal fizzled in the Legislature five years ago, but he planned to make a push to reintroduce a plan in the future.

“I don’t think people are opposed to the idea of giving relief to counties to prevent people from going to prison,” he said. “How we determine a formula for when that occurs is the rub.”

It costs $3,000 to enroll someone in drug treatment court for 12 to 18 months, compared with $30,000 to incarcerate someone for that same length of time, Hopwood said.

During the first phase of the drug court in Milwaukee, which ran from October 2009 to January 2011, 16 of the 31 enrolled offenders successfully completed the program.

The 52 percent passage rate is on par with the national average, Ashley said, and illustrated the kind of savings that could be realized by the criminal justice system.

Criminal defense lawyer Bill Reddin said he had no major criticisms of the Milwaukee program, other than he would like to get more clients enrolled.

The Milwaukee-based Reddin, Singer & Govin LLP attorney recently had a client removed from the program and subsequently denied reentry. He said some lawyers might be skeptical that a 52 percent success rate didn’t qualify the program as successful. But in his experience, success is measured more in the type of offender that qualifies for the program.

“You want a program that pushes the boundaries a little bit,” Reddin said. “You don’t want truly dangerous people on the street, but if you only accept people that are likely to be successful, the statistics will reflect that.”

There are 83 people active in the program, and since the start of the year, 16 have graduated. Ashley said the grant money allowed for 100 people to be enrolled at once, although entry was not easy.

Only 20 percent of offenders referred to the program are eligible, Hopwood said, because many don’t meet the nine-month sentence threshold or have previous violent crime convictions, which eliminate them from consideration.

The program requirements help to minimize any perception that the system is only looking for easy cases, Hopwood said.

“Once they are eligible, we’re not nitpicking at that point,” he said.

Martinez acknowledged that he probably was one of the tougher cases, and he entered the program with little optimism.

Random drug tests, regular meetings with Ashley and Martinez’s family and drug counseling were all part of the program.

“There was a time when I just wanted to leave,” he said. “Screw this. If they caught me they caught me, I’ll do the time.”

But he realized that going back to prison would do nothing to solve his addiction problem.

“Jail doesn’t help you stop doing drugs,” Martinez said. “They just lock you up and you are there thinking about getting out and using again.”

Legal News

- State Bar leaders remain deeply divided over special purpose trust

- Former Wisconsin college chancellor fired over porn career is fighting to keep his faculty post

- Pecker says he pledged to be Trump campaign’s ‘eyes and ears’ during 2016 race

- A conservative quest to limit diversity programs gains momentum in states

- Wisconsin prison inmate pleads not guilty to killing cellmate

- Waukesha man sentenced to 30 years for Sex Trafficking

- 12-year-old shot in Milwaukee Wednesday with ‘serious injuries’

- Milwaukee man convicted of laundering proceeds of business email compromise fraud schemes

- Giuliani, Meadows among 18 indicted in Arizona fake electors case

- Some State Bar diversity participants walk away from program

- Wisconsin court issues arrest warrant ‘in error’ for Minocqua Brewing owner

- Iranian nationals charged cyber campaign targeting U.S. Companies

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula