The criminalization of business

By: David Ziemer, [email protected]//March 28, 2011//

On day one in criminal law class, students learn about mens rea: a guilty mind as well as a guilty deed is a necessary element for a criminal prosecution.

On day one in criminal law class, students learn about mens rea: a guilty mind as well as a guilty deed is a necessary element for a criminal prosecution.

But in recent years, the erosion of that requirement has led to an explosion of criminal prosecution, or at least its threat, for business activities in which criminal intent is lacking.

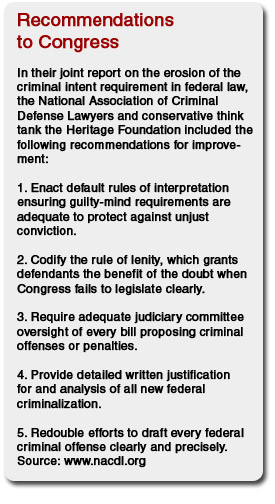

Last year, the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers teamed up for a joint project to examine “How Congress is Eroding the Criminal Intent Requirement in Federal Law.”

They concluded, as the title suggests, that federal regulatory statutes lack sufficient element of intent to warrant criminal prosecution.

The report acknowledges that, for crimes involving inherently wrongful conduct, the law properly allows the inference of a guilty mind. But it argues that for regulations which criminalize conduct that is not inherently wrongful, but is wrongful only because it is prohibited by law, that inference is unjust.

As a result, “neither criminal law professors or lawyers who specialize in criminal law can know all of the conduct that is criminalized. Ordinary individuals are at an even greater disadvantage.”

Citing the report, Milwaukee attorney Raymond Dall’Osto said, “Today, everything can be charged as a federal crime.”

In the absence of specific intent elements in the regulatory area, Dall’Osto, an attorney with Milwaukee-based Gimbel Reilly Guerin & Brown LLP, said strict liability has become the norm.

“My clients complain that they need a lawyer to do anything,” he said. “That’s some hyperbole, but there’s some legitimacy to it.”

Nathan Fishbach, a Milwaukee defense attorney with Whyte Hirschboeck Dudek SC, emphasized the difference between street crime and white-collar crime.

“Prosecuting people engaged in a legal business for doing illegal things is very different from prosecuting people who are in an illegal business to start with,” he said. “When a defendant is in a legal business, the first questions are, ‘Did he even do anything wrong?’ and ‘What was his intent?’”

In contrast, when someone robs a bank, Fishbach said, the answers to those questions are self-evident.

“But in white-collar cases,” he said, “the number one question is, ‘Is this a crime?’”

A shift in national priorities is clear when it comes to prosecuting business-related crime, according to statistics from the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. From 2009 to 2010, there was a 48 percent increase in federal prosecutions for hazardous waste treatment, disposal and storage. In contrast, prosecutions for drug offenses went down more than 13 percent from 2003 to 2010.

What’s driving the change, Fishbach said, is an emphasis on deterrence.

What’s driving the change, Fishbach said, is an emphasis on deterrence.

“Generally, the federal government’s criminal prosecution of white-collar offenses is predicated upon its position that this is necessary to achieve maximum deterrence,” he said. “The government’s belief is that a civil penalty is viewed ‘as a license to do business.’”

Daniel J. Vaccaro, a leading member of Michael Best & Friedrich’s Government Investigations, Compliance, and White-Collar Criminal Defense Team, attributes the growth in white-collar prosecutions to three factors: financial incentives, expanded target areas and the absence of mens rea.

Prosecuting white-collar crime often results in a windfall for the government in the form of fines, Vaccaro said. Attorney General Eric Holder testified to Congress on March 1 that, “in (fiscal year) 2010, the Criminal Division participated in efforts, including joint enforcement actions with our U.S. Attorneys’ Offices throughout the country, that secured more than $3 billion in judgments and settlements.”

“Unlike most drug defendants,” Vaccaro said, “the DOJ can recover money from corporations.”

Expanded definitions of what constitutes a crime also have contributed to the increase in prosecutions, he said. Criminal offenses are now sprinkled throughout both the U.S. Code and the Code of Federal Regulations.

The erosion of traditional mens rea requirements is the final factor, he said.

“‘Willfully’ and ‘corruptly’ have been replaced with ‘knowingly,’” he said. “Defendants need only have done the act, even if they didn’t know it was illegal.”

David Ziemer can be reached at [email protected].

Legal News

- More human remains believed those of missing woman wash up on Milwaukee Co. beach

- Vice President Harris returning to Wisconsin for third visit this year

- Wisconsin joins Feds, dozens of states to hold airlines accountable for bad behavior

- Trump ahead of Biden in new Marquette poll

- Bankruptcy court approves Milwaukee Marriott Downtown ‘business as usual’ motion

- New Crime Gun Intelligence Center to launch in Chicago

- Arrest warrant proposed for Minocqua Brewing owner who filed Lawsuit against Town of Minocqua

- Wisconsin Supreme Court justices question how much power Legislature should have

- Reinhart named the 2024 Wisconsin law firm of the year by benchmark litigation

- Milwaukee’s Common Council now has the most African Americans, women and openly LGBTQ members ever

- Office of School Safety Provides Behavioral and Threat Assessment Management Training Ahead of 25th Anniversary of Columbine Shooting

- Wisconsin Supreme Court to hear arguments in Democratic governor’s suit against GOP-led Legislature

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula