Program helps people overcome heroin addiction

By: Associated Press//December 26, 2017//

By DENEEN SMITH

Kenosha News

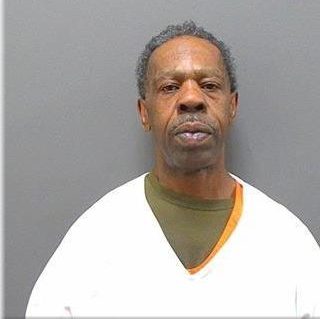

KENOSHA, Wis. (AP) — In the 12 years since he became a heroin addict, Labiano Valdez has tried to quit again and again.

He tried inpatient treatment. He tried supported detox. He tried the supportive prescription drug treatments methadone and Suboxone.

“I tried all that. None of it worked,” Valdez told the Kenosha News.

Since April, he’s been in Kenosha County’s Comprehensive Alcohol and Drug Treatment Program. The program uses a combination of therapy, one-on-one recovery specialists and treatment with the opiate-blocking drug Vivitrol to help heroin addicts into recovery.

For Valdez, the program has been a lifeline.

“I took a chance on it, and it is the greatest thing that ever happened to me,” he said.

Kenosha County launched the Vivitrol program in 2016. John Jansen, director of the county Human Services Department, said County Executive Jim Kreuser, alarmed by the growing number of heroin overdose deaths in the community, directed the agency to come up ideas for a county treatment program.

A group of agencies working together, including Humans Services, the Health Department, Disability and Aging Services and Community Impact Programs Inc., which contract to provide services with the county, came up with a pilot program.

“This program is more than just medically assisted treatment,” Jansen said.

Along with the monthly Vivitrol shot, there is weekly individual counseling and group counseling.

And in what organizers say is a key to the success of the program, each person enrolled is matched with a “recovery specialist” who provides practical and emotional support.

“It’s someone who works with them regarding housing, employment, who helps them work on insurance. It’s someone they can turn to 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for help,” said Chris Schoen, vice president of Community Impact Programs.

Each person in the program also gets medical treatment through either a monthly Vivitrol shot or a prescription to Suboxone.

For years, the standard for medically assisted treatment of heroin addiction has been methadone or Suboxone. Both drugs are “opioid agonists,” meaning they work with the brain’s opioid receptors much like heroin, blocking withdrawal symptoms of the drug without producing the same high as heroin.

Those drugs have years of clinical study backing up their use as an effective medical treatment for opioid addiction, and have been shown to reduce the risk of overdose death.

But they are also sometimes abused, and some proponents of 12-step recovery programs frown on the treatment, seeing it as a mask for addiction rather than a path to recovery.

Vivitrol was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of alcoholism in 2006 and for opioid treatment in 2010.

Vivitrol is an “opioid antagonist,” meaning it blocks drugs like heroin from producing a high.

It has less clinical data backing its use than the older treatments, but a National Institute on Drug Abuse-sponsored clinical study released in 2017 showed Vivitrol is as effective as Suboxone in a clinical trial.

The study found that about half of addicts using either treatment were free from relapse six months after treatment.

Schoen said people in the county program need to commit to taking either Vivitrol or Suboxone. “It’s really a conversation about where they are at and what works for them,” he said.

The challenge for Vivitrol treatment is that addicts must go through withdrawal before beginning treatment.

For the county program, participants must be clean from heroin use for seven to 10 days to be admitted to the program. People can take Suboxone immediately.

But, according to Schoen, the vast majority of the people in the program have chosen Vivitrol. “We only have a handful on Suboxone,” he said.

Schoen said when the pilot program began, it targeted addicts who were being released from Kenosha County Jail.

That was the case for Valdez, who, like many addicts, had a history of retail theft convictions. He had just been in the Kenosha County Detention Center for 85 days, and had gone through the Living Free treatment program there.

“So if you are locked up, and you are doing treatment through there, and you wanted to try to remain addiction free, you could ask to be in the program,” Schoen said. “We began taking people literally the day they were discharged, picking them up from jail, and taking them over to the treatment center to get their shot.”

As the county began to see success with the program, Jansen said, it began to expand beyond that pilot. Now, anyone from the community can ask to be in the program.

“We started in jail because that was a population we knew would be clean … but expanded in a matter of three or four months into the community,” Schoen said. “Now … I just get phone calls. People will call and say, ‘I really need help.'”

In 2018, the program has funds to treat about 50 to 55 people at a time.

To date, Schoen said, more than 100 people have started the Vivitrol program. Of those, he said, about two-thirds have remained in the program. Only 5 percent of those have had relapses.

Schoen said the success rate of about 65 percent is well above the national average for treatment programs.

Traditional outpatient programs have a success rate of 30 to 35 percent,” he said.

Twenty-seven people have graduated from the program. So far, he said, none of those have relapsed. He doesn’t expect that statistic to keep up, saying it is inevitable that some people will relapse.

Not everyone who inquires about the program gets in. People have to commit to spending six months in the program. They have to be off heroin for at least 7 to 10 days to qualify for Vivitrol. They need a medical screening to make sure they have liver function that will support use of the drug.

Jansen said no one is turned down because of money.

The county tries to get participants who are eligible for Medicaid enrolled in it because it will cover the cost of the drug — Vivitrol costs about $850 per shot.

But he said no one is turned away because they do not have insurance.

Lavern Jaros, director of the Division of Aging and Disability Services, said about $346,000 in county levy will go toward the program in 2018. Additional funding comes from state and federal grants and Medicaid reimbursement.

Valdez said that the program has given him a chance to recapture his life.

“Heroin is the toughest drug to kick — you wake up day after day, sick,” he said. “The struggle is real when you are on heroin. All you do is hustle (to get your next high).”

He said the Vivitrol program took away his cravings and helped him shift his mindset. He said he has reconnected with his family, is trying hard to be a good parent and has a job in a business making countertops, the first real job of his life.

“I’ve got a good job. I completed probation (successfully) for the first time in my entire life yesterday. I got my own place for the first time too,” Valdez said. “It’s given me a different outlook. It’s pushed me to be different.”

Legal News

- FBI launches criminal investigation into Key Bridge collapse

- Man charged in slaying after woman’s leg found at Milwaukee-area park

- Minnesota man guilty in fatal stabbing of teen on Wisconsin river, jury finds

- Wisconsin teen sentenced in bonfire explosion that burned at least 17

- Wisconsin man who broke into home, ate victim’s chicken, slept in victim’s bed, receives prison and jail sentences

- Judge refuses to dismiss Hunter Biden’s gun case

- House passes reauthorization of key US surveillance program after days of upheaval over changes

- Milwaukee Police officer traveling to Georgia training retires before facing discipline

- Evers to ask legislature to approve largest increase in state support for UW System in two decades

- 7th Circuit Court of Appeals proposes new rules

- Federal agencies allege toxic work environment for women in new report

- Wisconsin man sentenced for sex trafficking a woman and a minor online

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula