Up in the air: Drones changing legal field despite lack of regulation

By: Erika Strebel, [email protected]//September 1, 2015//

Up in the air: Drones changing legal field despite lack of regulation

By: Erika Strebel, [email protected]//September 1, 2015//

As far as Mark Meier is concerned, drones will one day replace the GoPro camera and selfie stick.

Following a recent thunderstorm, the hobbyist aerial photographer used his drone — or “quadrotor,” as he prefers to call it — to photograph the sky as it grew clearer above his hometown of Brookfield.

“I think it’s a hoot and a lot of fun,” Meier said. “You get wonderful footage that you’d never get if you were just flying in a hot air balloon or airplane.”

Meier has operated remote-control airplanes for more than 30 years, making for a smooth transition to drones. Such extensive experience, though, is far from prerequisite for taking up drones as a hobby.

With increased interest in the unmanned aircraft have come calls to revise the law to curtail various foreseeable dangers. No one is exactly sure, though, what the changes are most likely to be.

One source of complication is simply the technology’s newness. Drones have not been around long enough yet for the courts to set precedents that can guide drone regulation or clarify how the technology fits in with current law.

Russ Klingaman, an aviation lawyer, and Tom Schrimpf, an insurance lawyer, both with Hinshaw & Culbertson LLP of Milwaukee, have made it a point in recent years to keep tabs on the increasing use of drone technology. Their goal, they say, is to figure how the trend will ultimately reshape the law.

Dodging danger

Schrimpf’s and Klingaman’s greatest anxieties stem from drones often occupying the very same airspace as a variety of other sorts of flying objects.

“The biggest issue is the safety,” Klingaman said. “Somebody in their backyard with a small (drone) could decide to fly it low across the local highway or the interstate. … In terms of comparing them to birds, these are big, fast, powerful birds. They’re not little sparrows. People will get hurt.”

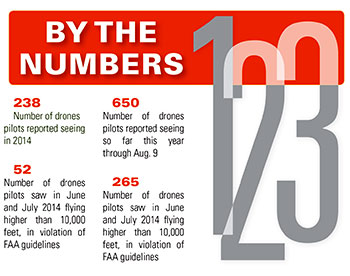

In a sign that the situation might be getting slightly out of control, more and more pilots are reporting seeing unauthorized drones, according to data compiled by the Federal Aviation Administration. Making matters worse, no law now requires hobbyists to communicate their flight plans with pilots of commercial aircraft or other drones.

That lack of oversight, Klingaman said, is troublesome for a number of reasons. If a drone hits a commercial airliner, the pilot will most likely not know how to identify the source of the crash or where to go to find it. And even if the drone were tracked down, the owner would be under no obligation to have a license or register himself in some other way. Knowing who should be sued becomes difficult.

Got insurance?

Drones aren’t simply sharing the skies with other aircraft. They can collide with cars and people, or even hit houses and buildings.

The dangers are not lost on Meier. Something all hobbyists like him must think about, he said, is insurance.

“That’s going to be a huge issue, maybe not for massive destruction,” said Meier, “but if you fall out of the sky and hit someone’s windshield, that’s a lot of damage.”

He said that buying a drone is not difficult.

“The concern is that people getting into it now can get a very sophisticated machine for not a lot of money without ever having flying anything remote control before,” Meier said.

Drones become particularly dangerous if they lose a GPS signal. In the absence of electronic guidance of that sort, operators have nothing but their own ability to fall back on to ensure the unmanned vehicles are flown safely.

“People say it’s as easy as pointing and clicking,” said Meier. “It’s not. In an ideal situation, it may be.”

The scarcity of experienced and competent operators, both Schrimpf and Klingaman said, is likely to provide fodder for many future personal-injury lawsuits. Hence the two lawyers’ recent interest in figuring out how drones affect insurance cases.

The technology has already opened new opportunities to sell coverage to those who fly drones for business purposes.

“Certainly you wouldn’t want to be operating one of these for commercial purposes and have something go wrong and have a claim for personal injury or property damage and not be able to tender it to your insurer,” Klingaman said.

In contrast, if a large aircraft is hit by a drone, or otherwise collides with one, it’s likely that neither the pilot nor the airline — nor the passengers for that matter — will ever receive compensation.

“The chances of me knowing who was at fault, what caused it and getting compensation, in this day in age, are probably not very good,” Klingaman said.

Klingaman and Schrimpf recently published an article reporting their findings from a wide review of homeowners’ insurance policies. Through their research, they discovered that most policies of that sort contain provisions making insurance coverage stop short of applying to damage caused by aircraft. The same policies also seek to have courts define “aircraft” to include drones.

There is an important exception, though. Reviewing the same insurance agreements, the two lawyers often come across separate provisions stipulating that coverage would in fact extend to damage from a model aircraft. With that apparent discrepancy, Schrimpf said, there is at least a possibility that insurance companies will find themselves having to pay for damage caused by a drone.

“It’s hard to say how the insurance market will react to that, whether they will write their policies to exclude that coverage or require a special writer to include it if you’re going to operate drones,” he said. “That’s something to watch as the market develops.”

Fast and loose rules

Although various states, including Wisconsin, have passed laws regulating drones, most of the new strictures are aimed at protecting privacy rather than mitigating danger. Wisconsin’s first drone law, passed in 2014, requires law enforcement officials to obtain search warrants before using a drone to collect evidence.

The law further imposes criminal penalties and jail time to those who use drones to attack someone or to photograph or record a person who could be presumed, at the time, to have a “reasonable expectation” of privacy.

Signs are abundant that government officials are aware that more regulation is likely needed.

In February, the Federal Aviation Administration released a series of proposed regulations that, if eventually approved, would set tighter restrictions on the use of drones. Elsewhere, existing rules already buried in the federal aviation regulations are likely applicable to some extent, Klingaman said.

In February, the Federal Aviation Administration released a series of proposed regulations that, if eventually approved, would set tighter restrictions on the use of drones. Elsewhere, existing rules already buried in the federal aviation regulations are likely applicable to some extent, Klingaman said.

For the time being, though, the main guidelines relied on by Meier and other hobbyists are those described in an FAA circular dating to 1981, as well as rules outlined in federal aviation regulations and in a safety code issued by the Academy of Model Aeronautics. In general, the regulations call for operators to keep drones within sight and away from groups of people, no more than 400 feet above the ground, and at a safe distance from airports or other places with heavy air traffic. If a drone is to be flown within 3 miles of an airport, the operator is supposed to at least let officials in the control tower know.

It’s not clear, though, how great of difference all this is making.

As long as the guidelines remain vague and enforcement lax, operators will be largely left to themselves.

“They’re not supposed to go higher than 400,” said Klingaman, “but it’s an honor system.” Follow @erikastrebel

Testing the laws

Because drones are a fairly new type of technology, there is little case law to give lawyers guidance in litigating cases involving them.

In Wisconsin, a case has yet to advance far enough for a precedent to be set. The situation might be about to change, though.

Many observers are watching a dispute between Chippewa Sand Co. and the operators of a drone flown over one of the company’s frack sand mines. Chippewa Sand argues that the flight path set the stage for a violation of the state’s new drone law, which is largely aimed at protecting privacy.

The law was broken, according to the company, when the operators used the drone to take pictures of a frack mine in the town of Cooks Valley. If Chippewa Sand chooses to pursue the dispute in court, the resulting case is likely to be widely seen as a test of the new law. Specifically at issue will be a provision prohibiting the use of drones to photographing or recording at times where there is a “reasonable expectation” of privacy.

Otherwise, the most significant case so far concerning drones, according to aviation law expert Russell Klingaman, is FAA vs. Pirker. Rather than privacy protections, that case concerns a rule prohibiting the careless or reckless operation of aircraft. The rule is one of many possibly pertinent ones that are now buried in federal aviation regulations, he said.

In 2011, the FAA sued Raphael Pirker for using a drone to make aerial photographs of the University of Virginia. He argued that his drone was in fact a model aircraft and thus was exempt from the ban on reckless operation. An administrative law judge initially sided with Pirker, but that decision was reversed by the National Transportation Safety Board in November 2014.

In reaching its decision, the board looked back to the Federal Aviation Act of 1958. That act, the board decided, defined the word “aircraft” in a way that includes drones.

— Erika Strebel

Legal News

- Some State Bar diversity participants walk away from program

- Wisconsin court issues arrest warrant ‘in error’ for Minocqua Brewing owner

- Iranian nationals charged cyber campaign targeting U.S. Companies

- Facing mostly white juries, are Milwaukee County defendants of color truly judged by their peers?

- Milwaukee Mayor speaks in D.C. Tuesday at White House water summit

- Chicago man sentenced to prison after being caught with ‘Trump Gun’

- FTC bans non-competes

- Gov. Evers seeks applicants for Dane County Circuit Court

- Milwaukee man charged in dismemberment death pleads not guilty

- Democratic-led states lead ban on the book ban

- UW Madison Professor: America’s child care crisis is holding back moms without college degrees

- History made in Trump New York trial opening statements

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula