The price of wrongful incarceration

By: Dan Shaw, [email protected]//October 21, 2013//

New legislation seeks to change who can decide and how much to give

Annette Bruner’s son meant much more to her than $25,000.

But now that he’s dead from a suspected suicide following wrongful incarceration, the money, she said, is all that is left to fight for.

It’s a battle that already has cost Bruner, her late husband and her late son, Forest Shomberg, $77,500 in legal fees. But it is unclear if she can recoup the $25,000, the maximum Wisconsin will grant to compensate someone wrongly incarcerated in the state, plus the tens of thousands in fees spent trying to prove Shomberg’s innocence.

If Bruner’s arguments fail to move the Wisconsin State Claims Board, which is charged with awarding restitution to the wrongfully convicted, she said, she doubts she can afford to fight the decision in court. Bruner said she and her late husband spent much of their money trying for years to prove the innocence of her son, who was imprisoned from 2003 to 2009 before DNA evidence ruled him out as the culprit in an attempted sexual assault.

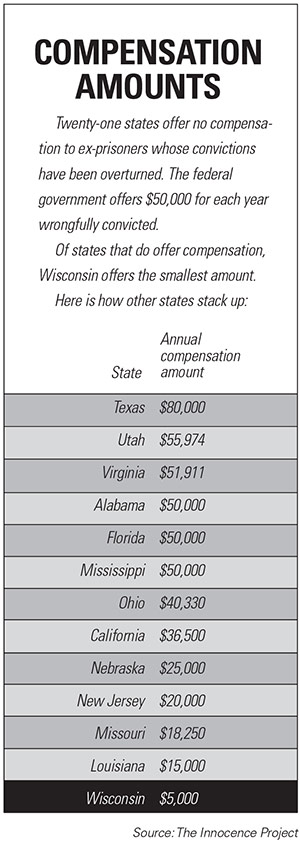

Some state lawmakers are fighting a battle parallel to Bruner’s. They have proposed a bill that would make clear that compensation for wrongful incarcerations can go to the relatives of people who die while seeking restitution from the state. The same legislation would increase to $50,000 the maximum compensation a person can receive for each year of wrongful imprisonment and provide the wrongfully incarcerated with services to help them rejoin society.

And in the proposed change that could have had the greatest effect in Shomberg’s case, the legislation would take away from the claims board the responsibility of awarding such money.

The board in December ruled Shomberg had not produced “clear and convincing” proof of his innocence. Months later, though, Shomberg prevailed on an appeal to Eau Claire County Circuit Judge Michael Schumacher, who ordered the claims board to award him “an amount of money that will equitably compensate” him.

But before Shomberg could appear before the board again, he died from a heroin overdose, which Bruner said was probably a suicide. Click here to subscribe to Wisconsin Law Journal today

“I’m not blaming them for his death,” Bruner said. “But I just think it’s wrong. You don’t falsely accuse someone and then blow it off and then say, ‘Gee, we’re sorry about it. We took six years of your life.’”

In place of the claims board, the bill would assign the responsibility of awarding compensation to administrative law judges in the state Department of Administration.

Byron Lichstein, a co-director of the Wisconsin Innocence Project, which represented Shomberg in his first attempt to obtain restitution, said he does not consider the proposed change to be a rebuke of the claims board’s work. The bill, which the Innocence Project helped write, seeks to ensure justice is served as promptly as possible, Lichstein said.

READ OUR RELATED EDITORIAL: Making up for lost time

A particular concern about the current system, he said, is that the claims board meets only four times a year, often forcing exonerees to wait months to get a hearing.

Lichstein also said the board — composed of lawyers from the governor’s office, the Department of Justice and the Department of Administration, as well as a state representative and senator — lacks the extensive fact-finding powers a judge can use to bring a case to a prompt and satisfying conclusion.

Lichstein also said the board — composed of lawyers from the governor’s office, the Department of Justice and the Department of Administration, as well as a state representative and senator — lacks the extensive fact-finding powers a judge can use to bring a case to a prompt and satisfying conclusion.

“I think they were doing the best they could do,” he said.

But Schumacher was not the only judge in recent times to call into question the board’s decisions. David Turnpaugh, a Milwaukee man who appeared at the same December claims board hearing as Shomberg, has appealed the board’s decisions twice in court and won.

Turnpaugh’s dealings with the claims board originated from his 2006 exoneration from a prostitution charge. On appeal, a judge decided the act Turnpaugh was arrested for, asking someone to masturbate in exchange for money, was not a crime in Wisconsin.

In Turnpaugh’s first appearance before the claims board, it ruled that he, like Shomberg, had not furnished clear and convincing proof of his innocence. That decision drew a stinging rebuke when Turnpaugh challenged it in court. The Wisconsin Court of Appeals released an opinion in May 2012 that stated, “the claims board’s legal conclusions are wholly unreasonable and directly contravene the statute it is charged with administering.”

The court went on to conclude that because Turnpaugh was incarcerated for an act that does not constitute a crime in Wisconsin, he was “innocent as a matter of law.”

“The claims board’s finding to the contrary,” the appeals opinion stated, “is inexplicable.”

The court sent the case back to the claims board with instructions to determine equitable compensation. But Turnpaugh’s travails were not over.

At his second hearing before the board, the members cited a rule that prohibits compensation from going to someone who has contributed to his own wrongful incarceration. In Turnpaugh’s case, the board noted the courts had accepted a female undercover police officer’s testimony as proof that Turnpaugh had made some sort of proposition. Because Turnpaugh’s statements had led to his arrest, regardless of whether what he said was illegal, the board reasoned, he was partly responsible for what happened to him.

Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Paul Van Grunsven, who took up Turnpaugh’s appeal of the claims board’s second decision, deemed the outcome “absurd.”

“Under the claims board’s interpretation,” the judge wrote, “a person wrongly charged with intent to buy drugs would not be eligible for compensation simply because they were standing on a corner in a bad neighborhood having a conversation with a known drug dealer.”

Turnpaugh said that before he took his fight to the courts, several people had told him, “You can’t beat the claims board.” He said he now thinks his difficulties with the board are part of the reason lawmakers are considering making judges responsible for awarding compensation.

“They didn’t even see the most basic of legal arguments,” Turnpaugh said, “and they aren’t bad lawyers. The admonishment from the courts makes it clear they can’t effectively make these decisions.”

Supporters of the proposed legislation say the changes they want do not stem from any particular case.

But two of the proposals could have made a difference for Turnpaugh. The bill would eliminate the ban on compensation going to those who contributed to their own wrongful incarceration and would replace the standard demanding clear and convincing evidence of innocence with the “preponderance of the evidence” standard used in most civil cases.

Keith Findley, a law professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a director of the Wisconsin Innocence Project, said the first proposed change is important because false confessions are one of the chief causes of wrongful imprisonment. And the switch to the preponderance of the evidence standard is fair, Findley said, because in asking someone to prove his innocence, the state is asking for proof of a negative, which is notoriously difficult to furnish.

But if one member of the claims board, State Rep. Pat Strachota, R-West Bend, has her way, the legal standards will remain as they are and the responsibility of awarding compensation will stay with the claims board.

Strachota, the only member of the claims board who could be reached for this story, said she was not consulted on the proposed legislation. She said she supports the proposed move to increase compensation but is working on her own alternative legislation.

Strachota said critics should remember the board was never meant to be a surrogate for a court of law. The board relies on the clear and convincing standard, she said, because lawmakers wanted to prevent someone who gets off on a technicality from collecting state money.

The board especially wants to avoid, she said, compensating someone such as Steven Avery of Two Rivers, who in 2004 was awarded nearly $49,000 for a false rape conviction, only to commit a rape and murder about a year later.

“The question of what is fair,” Strachota said, “it’s a very difficult question when someone has been wrongfully convicted.”

Whatever changes are made to the law, they probably would occur too late to make a difference for Bruner, who is scheduled to appear before the claims board in December. She said her only hope is that the board members understand her son’s wrongful conviction was an injustice to more than one person.

“He was the only family I had left,” Bruner said. “It really makes me angry in many respects. You don’t just do this to somebody.”

Proposed legislation suggests several changes

Beyond taking compensation decisions out of the hands of the State Claims Board, a bill dealing with the wrongfully convicted would:

- increase from $5,000 to $50,000 the compensation for each year a person spends behind bars on a wrongful conviction. The bill also would eliminate the rule limiting total compensation to $25,000.

- provide social services to the wrongfully incarcerated upon their release. The services would be similar to those offered to prisoners upon their release.

- allow exonerated ex-prisoners to be added to the health care plan offered to state employees.

- expunge convictions that have been overturned from the state’s Wisconsin Circuit Court Access website

- prevent someone who commits a violent felony after being exonerated of another conviction from obtaining state compensation

- allow those who are exonerated to be compensated, within reason, for attorney’s fees

- allow public defenders to represent those who have been exonerated in their attempts to win compensation.

Legal News

- Chicago man sentenced to prison after being caught with ‘Trump Gun’

- FTC bans non-competes

- Gov. Evers seeks applicants for Dane County Circuit Court

- Milwaukee man charged in dismemberment death pleads not guilty

- Democratic-led states lead ban on the book ban

- UW Madison Professor: America’s child care crisis is holding back moms without college degrees

- History made in Trump New York trial opening statements

- Prosecutor won’t bring charges against Wisconsin lawmaker over fundraising scheme

- Republican Wisconsin Senate candidate says he doesn’t oppose elderly people voting

- Vice President Harris to reveal final rules mandating minimum standards for nursing home staffing

- Election workers fear threats to their safety as November nears

- Former law enforcement praise state’s response brief in Steven Avery case

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula