Passing the gavel: Judicial retirements leave gaps in state, federal court systems

By: Amy Karon, [email protected]//October 15, 2012//

Passing the gavel: Judicial retirements leave gaps in state, federal court systems

By: Amy Karon, [email protected]//October 15, 2012//

Iowa County Circuit Judge William Dyke is 82, but has no plans to step down from the bench and said he is disappointed when he sees aging colleagues do so.

“It’s difficult to lose some of these folks. I have not encouraged one to retire,” said Dyke, who this summer was elected chief of the state’s 10 chief judges. “I feel the public suffers from losing long-term judges who have seen it all and know exactly where the nerve points are in a case.”

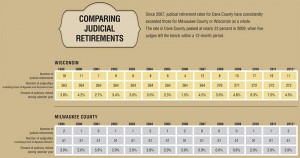

Dyke has had reasons for disappointment lately. Since 2009, the average rate of judicial retirements from Wisconsin state courts increased by 75 percent compared to the period from 1999 to 2009.

Former Dane County Circuit Judge Patrick Fiedler said he remembers when five judges retired in Dane County within four months in 2009. Their reasons were varied, he said.

John Voelker, director of the State Courts Office, said passage of Wisconsin’s budget repair bill contributed to the spike in retirements as uncertainty about changes in pensions and benefits motivated some judges to leave the bench.

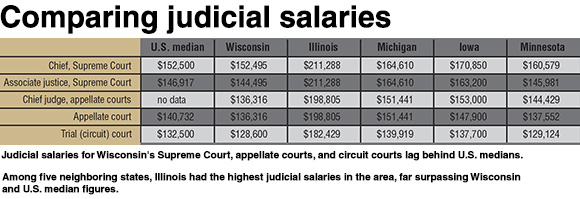

Wisconsin’s judicial salaries, which are less than those in neighboring states, don’t help, said retired Dane County Circuit Judge Sarah O’Brien. There is less motivation to stay on versus pursing other interests in retirement, she said, or going into private practice.

Experience lost

The resulting shift is noticeable, O’Brien said. While newer judges bring fresh energy and new ideas, she said, they also lack experience.

“The downside is: They have to make some of the same mistakes we made 10, 15 and 20 years ago,” said O’Brien, who retired in May. “The loss of that institutional knowledge and memory is unfortunate. I found I really missed that after all the more experienced judges had retired.”

The public also feels the loss of experienced judges. Wisconsin courts are taking longer to respond to public requests for information, said Daniel Hall, vice president of the National Center for State Courts’ consulting services division. And complex cases can go untouched for months between when judges step down and their replacements are appointed.

Reserve judges help manage simpler cases in those absences, Voelker said, but the state’s tight budget has led to decreased use of reserves, according to a survey published by the NCSC in November.

The NCSC found Wisconsin’s state court budget dropped by $1.8 million between fiscal years 2011 and 2012. In addition to decreasing use of reserve judges, Wisconsin courts have cut courts’ operating hours and furloughed and frozen the salaries of judges and court officials to save money, according to the NCSC study.

So far, the state has avoided increased case backlogs and longer case disposition times, according to the study and Wisconsin Law Journal’s separate analysis of 10 years of publically reported court disposition data.

“Our chief judges do a good job of figuring out how to keep the calendar moving,” Voelker said. “When you bring someone new in, it takes them a little while to get up to speed, depending on their background. But I think, overall, we do a really good job of judicial education.”

It’s hard to beat the efficiency of a veteran judge, however, said former Dane County Circuit Judge Daniel Moeser, who retired in 2011 after 32 years on the bench. Experienced judges “can cut through the baloney and decide things more efficiently and get to the right answers,” he said.

Wisconsin could soon be facing an even greater lack of experienced judges, as almost two-thirds of judges in the state court system within the next five years will reach that age of 62, which is the retirement qualification, Voelker said. Based on current judges’ ages, he said, that proportion will climb to 83 percent in the next decade.

Leaders in various professions across the country are retiring in greater numbers, he said, because baby boomers are now 48 to 66 years old.

That trend has spurred a national shortage of federal judges. Ninety-two federal judges took senior status in the first three years of the Obama administration, compared to 72 and 70 in the first three years of the Clinton and Bush administrations, respectively, according to a 2012 analysis by the Brookings Institution, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, D.C. As a result, federal district court judicial vacancies increased from 41 to 65 during Obama’s first three years in office.

Taking senior status lets federal judges cut their workloads while receiving full pay. To qualify, judges must be 65 or older, and their combined age and years of experience must total 80.

A University of Pennsylvania Law Review study of retiring federal judges found they are more likely to take senior status now because Congress has not increased federal judicial salaries since 1991.

Missed appointments

Federal judicial appointments also have lagged. In Wisconsin, the U.S. District Court for the Western District has lacked an active judge since former Judge John Shabaz assumed senior status in January 2009.

Shabaz died in August, but after more than 1,350 days since he took on senior status, his position remains vacant, according to the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. President Barack Obama has nominated former state Supreme Court Justice Louis Butler to fill the slot, but the Senate returned the nomination to the president three times and, so far, no nomination has been announced this year.

As a result, Wisconsin’s Western District is one of 31 federal courts in the country facing a judicial emergency in which there are not enough judges to do the work of the court, according to the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

Federal judges who retire or take senior status often can earn more working in alternative dispute resolution, the University of Pennsylvania study found. Retired Wisconsin judges often work in mediation or arbitration, too.

After retiring last year as the longest-serving judge in Dane County history, Moeser now works at Midwest Mediation LLC. Judge Gerald Nichol also has worked there since his 2004 retirement from the Dane County Circuit Court.

“I can now control my schedule a little better,” Moeser said. “Our mediation business is not full time. We can block off times we are not available.

“When you are on the trial court you are driven by the schedule. It is constant. It is a pressure that is always there, to process the cases, get them decided …”

Years of experience dealing with that pressure is exactly why seasoned judges need to stay on the bench, Dyke said.

“I don’t think retirements bode very well for the judiciary,” Dyke said. “The seasoning is really important.

“… Losing these judges, I think, is a loss to the profession generally and a loss to the public in that you really want the best.”

Judges enjoy ‘retirement’

Former Dane County Circuit Judge Patrick Fiedler knew it was time to retire from the bench last year when he started to covet the jobs of the lawyers appearing before him in court.

“When I was on the bench, I presided over a lot of trials,” he said. “I enjoyed all the interactions I had with lawyers connected to trying a case. I got to the point where I had a certain amount of envy for those lawyers.”

His retirement from the judiciary has not resulted in total retirement. Fiedler, 59, now works as an attorney at Axley Brynelson LLP. He puts in about 60 hours a week – more than when he was a judge. He’s also president-elect of the Wisconsin State Bar.

Fiedler’s not alone in his active post-judiciary life.

Former Dane County Circuit Judge Sarah O’Brien, who retired in May, now works as a reserve judge and volunteers with Safe Communities, a public-private partnership to combat Dane County’s heroin epidemic. She said her involvement stems from four years presiding over treatment court cases, which she called a highlight of her judicial career.

“I was always very involved in extracurricular activities,” she said, “whether it revolved around treatment court issues or benchbook or justice strategies. I loved being a judge.

“But I think I loved the extra activities as much, and I felt like I didn’t have the energy and enthusiasm to do both anymore.”

Former Milwaukee Municipal Judge James Gramling spends his retirement combating social problems, as well. Gramling helped found the nonprofit Center for Driver’s License Recovery and Employability, which helps low-income people get their suspended and revoked driver’s licenses reinstated so they can get jobs. He has worked for the center pro bono since 2007.

“I saw the issue in municipal court day-in and day-out,” Gramling said. “People could not navigate all of the systems necessary to get their licenses back. I saw it as a justice system issue. It tended to grind people up.”

After 21 years on the bench, Gramling said he was happy to let new judges take the lead at the courthouse.

“Some judges hold onto the job because they sense they own it, and they need to do that job,” he said. “And that is just not the case. Other people need to make their mark on the system.”

— Amy Karon

Legal News

- State Bar leaders remain deeply divided over special purpose trust

- Former Wisconsin college chancellor fired over porn career is fighting to keep his faculty post

- Pecker says he pledged to be Trump campaign’s ‘eyes and ears’ during 2016 race

- A conservative quest to limit diversity programs gains momentum in states

- Wisconsin prison inmate pleads not guilty to killing cellmate

- Waukesha man sentenced to 30 years for Sex Trafficking

- 12-year-old shot in Milwaukee Wednesday with ‘serious injuries’

- Milwaukee man convicted of laundering proceeds of business email compromise fraud schemes

- Giuliani, Meadows among 18 indicted in Arizona fake electors case

- Some State Bar diversity participants walk away from program

- Wisconsin court issues arrest warrant ‘in error’ for Minocqua Brewing owner

- Iranian nationals charged cyber campaign targeting U.S. Companies

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula