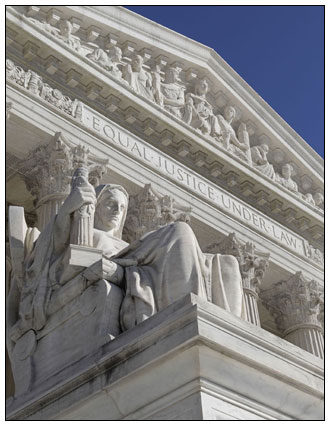

US Supreme Court takes on tolling securities case

By: KIMBERLY ATKINS, BridgeTower Media Newswires//December 5, 2011//

US Supreme Court takes on tolling securities case

By: KIMBERLY ATKINS, BridgeTower Media Newswires//December 5, 2011//

Sometimes at the U.S. Supreme Court, words and labels mean everything.

Sometimes at the U.S. Supreme Court, words and labels mean everything.

Last week, the justices parsed the wording of a securities law provision to determine whether to label it a statute of limitations or a statute of repose. The answer could have a tolling effect on the ability of shareholders who lost a fortune in the dot-com bust to sue for lost profits.

The case of Credit Suisse Securities v. Simmonds stems from a lawsuit filed by Vanessa Simmonds, who invested in tech stocks underwritten by Credit Suisse and other investment banks during the dot-com boom of the 1990s.

After the tech bubble burst in 2001, a host of underwriters were sued under securities and antitrust laws for allegedly defrauding the public by engaging in a host of accounting mechanisms that artificially inflated the price of the issuers’ securities to get a higher demand for their initial public offerings.

Simmonds is one of a group of shareholders who filed derivative suits under §16(b) of the Securities Exchange Act against 55 underwriters who were implicated in the IPO litigation to recover the realized profit from the alleged scheme.

The law provides that “no such suit shall be brought more than two years after the date such profit was realized.”

The underwriters moved to dismiss the cases as time-barred, and the district court granted the motion, finding that the facts giving rise to the claims were known by shareholders at least five years before the case was filed.

But the 9th Circuit reversed, holding that the statute of limitations was tolled because the underwriters failed to file proper disclosures for the alleged transactions as required by §16(a).

The underwriters appealed and the Supreme Court granted certiorari.

‘Plain vanilla statute of limitations’

Chief Justice John G. Roberts did not participate in hearing the case, presumably due to ownership of Credit Suisse-related stock.

During oral arguments, Christopher Landau, a partner in the Washington office of Kirkland and Ellis, argued that the two-year limit is a state of repose, not a statute of limitations, and therefore is not subject to equitable tolling.

“The statute doesn’t say ‘two years after the date the defendants filed a section §16(a) report’ [or] “two years after the date the plaintiff discovers’” the profit.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg questioned his assertion.

“It just has what seems to me a plain vanilla statute of limitations that is traditionally subject to equitable tolling,” Ginsburg said.

Justice Elena Kagan echoed Ginsburg’s sentiment.

“What takes you out of the default position, which [would mean] equitable tolling applies?” Kagan asked.

Landau said lawmakers chose the words carefully.

“Congress in the 1934 [Securities] Exchange Act was carefully attuned to the issue of time limits,” Landau said. “Congress thought long and hard about this.”

Even if the limitation is construed as a statute of limitations, Landau argued, the plaintiff should have been well aware of the cause of action years before the lawsuit was filed.

“Respondents have come and said, ‘Well, what we didn’t know [was that] the underwriters were in a conspiracy with the issuer insiders,” Landau said.

Ginsburg noted that the plaintiffs have the benefit of the doubt.

“You may well be right that they really knew or they should have known,” Ginsburg said. “But at this stage we can’t make that judgment because we have to accept the plaintiffs’ allegations as true.”

Landau noted that the plaintiffs rely, in their pleadings, on articles about the accounting practices that were published more than two years before the suit was filed.

“The pleaded facts by the plaintiff themselves show this is untimely as a matter of law,” Landau said.

Jeffrey B. Wall, assistant to the solicitor general, argued on the government’s behalf, but not in support of either party. Instead, he advanced the Justice Department’s position that the language creates a statute of limitations, not repose, which can be equitably tolled until the activity in question is discovered by shareholders.

“Well, if you were drafting a statute of repose, how would you phrase it other than the way this is phrased?” asked Justice Antonin Scalia.

“Normally what Congress does is it says there should be no jurisdiction after a particular time,” for repose statutes, Wall said.

Duty to read financial journals? Jeffrey I. Tilden of the Seattle firm Gordon Tilden Thomas & Cordell argued that the statute of limitations can be equitably tolled until the proper §16(a) disclosures are made, revealing the realized profit. Otherwise, he argued, the wrongdoers can stave off lawsuits by further violating the law.

“As a matter of logic, it makes no sense to provide the one who violates §16(b) an escape [from] liability because they also violate §16(a),” Tilden said.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted that the practices cited in the complaint had been “written about extensively for years and years.”

“So, what new information did you receive that told you that you should file a lawsuit?” Sotomayor asked.

Tilden argued that, without the withheld disclosures, the shareholders could not have reasonably been aware of the conduct.

“We cannot impose on a shareholder the obligation to read the Journal of Financial Management or to follow a Harvard symposium,” Tilden said.

Justice Samuel Alito wondered if a ruling for the shareholder would allow attorneys seeking to bring securities claims to search for potential plaintiffs who “purchased the stock long after all of this takes place,” did not read articles about it and “know nothing.”

Tilden said that is why Congress required the filing of disclosures.

“Congress told us to go look in one place, and not anywhere else,” Tilden said.

Scalia was still focused on the statute’s wording.

“I don’t know any other statute of limitations that achieves the result that you want that puts it that way,” Scalia said.

Tilden likened the situation to a statute of limitations on product liability suits. A consumer who buys a lawnmower won’t know of a defect when the lawnmower is made or purchased, but he will know once the machine malfunctions and rolls over his foot.

“You may not know anything about your state’s product liability act [but] you do know that you used to have ten toes and now you have nine,” Tilden said.

A decision is expected later this term.

Legal News

- Wisconsin joins Feds, dozens of states to hold airlines accountable for bad behavior

- Trump ahead of Biden in new Marquette poll

- Bankruptcy court approves Milwaukee Marriott Downtown ‘business as usual’ motion

- New Crime Gun Intelligence Center to launch in Chicago

- Arrest warrant proposed for Minocqua Brewing owner who filed Lawsuit against Town of Minocqua

- Wisconsin Supreme Court justices question how much power Legislature should have

- Reinhart named the 2024 Wisconsin law firm of the year by benchmark litigation

- Milwaukee’s Common Council now has the most African Americans, women and openly LGBTQ members ever

- Office of School Safety Provides Behavioral and Threat Assessment Management Training Ahead of 25th Anniversary of Columbine Shooting

- Wisconsin Supreme Court to hear arguments in Democratic governor’s suit against GOP-led Legislature

- Lawsuit asks Wisconsin Supreme Court to strike down governor’s 400-year veto

- Wisconsin man pleads not guilty to neglect in disappearance of boy

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula