Supplemental instructions should be rare

By: dmc-admin//February 11, 2004//

|

|

“Our system of justice should not permit the State also to ask for additional substantive instructions once it realizes why the jurors may be experiencing difficulties in reaching a verdict.” Hon. Patricia S. Curley |

It was error to instruct a jury on lesser-included offenses after the jury became deadlocked, the Wisconsin Court of Appeals held on Feb 3. However, the court acknowledged that it might not be error in rare circumstances.

Stefanie P. reported to the police that while she was walking home from work in the late evening of Sept. 8, 2001, a man came up behind her, grabbed her, pressed what she believed to be a knife against her throat, and pushed her across the street into a used car lot.

She reported that, once there, the man went through her empty pockets, opened a car door, pushed her inside and sexually assaulted her for approximately thirty minutes, all the while holding the knife. After her assailant laid the knife down on the dashboard, she escaped by pushing him, getting up, and running away. She ran to a corner tavern where she saw someone she knew, who then walked her home. Once home, Stefanie P. told a friend what had occurred. Her friend took her to a local hospital, and the police were called.

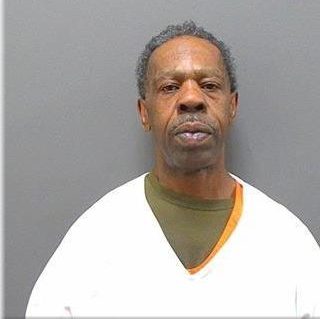

Stefanie P. identified Vaughn Thurmond as the assailant, and he was charged with first-degree sexual assault and kidnapping while armed. At the preliminary hearing, Stefanie P. admitted that, while she believed her assailant had a knife, she never actually saw it. She also testified that her assailant asked her for money. Thurmond was bound over for trial.

After the preliminary hearing, the State amended the complaint to add a count of attempted armed robbery to the original charges.

A jury trial was eventually held before Milwaukee County Circuit Court Judge Joe Donald, and both Stefanie P. and Thurmond testified. Stefanie P. described the events in a manner similar to her preliminary hearing testimony, except that she claimed to have seen the knife. Thurmond testified that his encounter with Stefanie P. was consensual.

After the testimony, the trial court held a jury instruction conference, at which neither party requested any instructions regarding lesser-included offenses.

The jury deliberated for several days, during which it asked a number of questions of the court. One letter to the court stated that three jurors “find Stefanie P.’s credibility in question.”

In another question, the jury inquired about lesser-included instructions, and the court informed the jury that it was not a proper question.

However, on the third day of deliberations, on motion by the State, over Thurmond’s objection, the court read the jury instructions for lesser-included offenses. The jury quickly found Thurmond guilty of second-degree sexual assault and kidnapping, but without the use of a dangerous weapon, and not guilty of attempted armed robbery.

Thurmond appealed, and the court of appeals reversed in a decision written by Judge Patricia S. Curley and joined by Judge Ted E. Wedemeyer. Judge Charles B. Schudson wrote separately, concurring in part, and dissenting in part.

Unfair Prejudice

The court concluded that the timing of the supplemental instructions was unfairly prejudicial because the jury had earlier been told that lesser-included instructions were inappropriate, and, by giving the lesser-included instructions late in the deliberations, the jury may have felt that the trial court was endorsing a finding of guilt to the lesser-included offenses.

The court acknowledged that sec. 805.13(5) permits trial courts to give supplemental instructions generally to the jury, even after deliberations have begun.

However, whether instructions on lesser-included offenses can be given is an issue of first impression in Wisconsin, so the court looked to other jurisdictions.

The court found that the weight of authority declines to adopt a per se rule against such instructions, and declined to do so, as well.

The court agreed with the Maine Supreme Court that, “A re-instructing presenting for the first time choices for lesser included offenses not presented in

the initial instructions, if proper at all, would be a rare event, only done in exceptional circumstances.” State v. LaPierre, 2000 ME 119, par. 21, 754 A.2d 978.

|

What the court held Case: State of Wisconsin v. Vaughn Thurmond, No. 03-0191-CR. Issue: Can a court give supplemental jury instructions on lesser-included offenses after the jury has deadlocked? Holding: No per se rule prohibits such instructions, but they should be given only in rare and exceptional cases.. Counsel: Ann T. Bowe, Milwaukee, for appellant; Robert D. Donohoo, Milwaukee; Marguerite M. Moeller, Madison, for respondent. |

The court noted a number of potential dangers from permitting such instructions. First, a stalled jury may regard the newly furnished theory of liability as the court’s recommendation to resolve the impasse by agreeing to the lesser offense.

Second, a jury might consider the last instruction as an intimation of the desire of the court that the defendant be convicted of some offense.

Finally, a defendant can be harmed by relying on a reasonable expectation that he faces exposure to liability only for the greater offense charged.

Summarizing the various cases in which courts reversed convictions because of lesser-included instructions, the court found, “when it appeared likely that the jury saw the belated instructions as a court recommendation to convict; when the timing of the instructions makes the new instruction appear overly significant, upsetting the orderly process of the trial and upsetting the defendant’s right to a fair trial; when the defendant’s presentation of his case is harmed; and when circumstances suggest the verdict was driven by a stalled jury’s desire to disband rather than complete a fair assessment of the evidence.”

Applying that standard, the court concluded the instruction was unfairly prejudicial in Thurmond’s case.

The court noted, “the jury’s request for lesser-included offense instructions was originally rebuffed by the trial court, and was only resurrected when the State requested them. We must conclude that this change of heart by the trial court would lead a reasonable jury to believe that the trial court was now endorsing the new instructions.

A juror might reasonably ask: why else would they be improper earlier, but proper now?”

The court also noted that not much time was spent after the instruction before returning a guilty verdict. The court concluded, “The rapid return of the verdict implicates another of the concerns voiced about this practice — the verdict may have been driven more by a stalled jury’s desire to be released from its duty than its having reached a fair decision.”

The court added, “The jury’s communication that it felt deadlocked and ‘needed a new way to deliberate’ points to the conclusion that the jury used the new offenses as a way of ending their deadlock rather than reaching a unanimous decision.”

The court further found that the circumstances suggested prejudice, noting, “The note sent by the jury indicated that three jurors questioned the ‘credibility of the victim.’ This note did not state that three jurors were unsure of whether a knife was used in the attack, but rather, that they did not believe the victim. Questioning the victim’s credibility could implicate any number of concerns besides the uncertain existence of a knife. Those jurors might have wondered whether there was actually an assault at all, or whether the manner in which it occurred or was described by the victim was believable.”

Even if the holdout jurors were concerned with the existence of a knife, the court concluded the verdict was still suspect, citing a similar case from Texas, Garza v. State, 55 S.W.3d 74 (Tex.Ct.App.2001).

In Garza, the defendant was charged with aggravated kidnapping — aggravated because of the alleged use of a knife. While the witness testified a knife was used, other witnesses stated they did not see a knife. The jury sent a note saying that three jurors would find Garza not guilty, and indicated that the use of a knife was the problem. The judge then instructed the jury on the lesser-included offense of kidnapping, over Garza’s objection, and the jury convicted him.

In reversing, the Texas court concluded, “The trial court’s decision to supplement the charge with the kidnapping charge effectively overrode the professional judgment of appellant’s counsel that there was not enough evidence to convict appellant on the

aggravated kidnapping charge and that the jury would have to acquit him.” Garza, at 77-78.

Analogizing the case to Thurmond’s, the court found that Thurmond’s strategy was to question the existence of the knife to challenge the truthfulness of Stefanie P.’s account of the incident. The court concluded, “permitting the State to have additional jury instructions read to the jury that rebut the very points the defense made in closing arguments is unfair. Our system of justice permits the State to challenge the defendant’s closing arguments in its rebuttal. It should not permit the State also to ask for additional substantive instructions once it realizes why the jurors may be experiencing difficulties in reaching a verdict.”

Accordingly, the court reversed.

The Concurrence/Dissent

| |

||

|

Links Related Article |

||

| |

||

Judge Schudson dissented, stating that, “For the most part, the majority has offered a thoughtful analysis with which I agree,” and concurring that, while there should be no per se rule against supplemental lesser-included offense instructions, they should be rare, and reserved for exceptional circumstances.

Schudson disagreed with the application of the principles adopted, however, and concluded that reversal is not required, but that the case should be remanded for an evidentiary hearing at the trial level.

Complaining about the adequacy of the record, Schudson found nothing in the record to indicate that the trial court ever communicated to the jury, at an earlier time, that a lesser-included offense instruction was improper.

Schudson also concluded that it is uncertain, from the jury’s note stating that questioned the “credibility of the victim,” whether they questioned the presence of a knife or something else.

Schudson wrote, “Here, as in [U.S. v. Welbeck, 145 F.3d 493 (2d Cir. 1998)]: (1) the jury’s question may have provided the initial impetus for the trial court’s consideration of the supplemental instruction; (2) Thurmond was not prejudiced, given that his consent defense, if believed, would have defeated an allegation of either first or second-degree sexual assault; (3) the trial court allowed defense counsel the chance to offer additional closing argument; and (4) a failure to offer the supplemental instruction could have defeated the ends of justice — a verdict resolving the case for both parties.”

Click here for Case Analysis.

David Ziemer can be reached by email.

Legal News

- FBI launches criminal investigation into Key Bridge collapse

- Man charged in slaying after woman’s leg found at Milwaukee-area park

- Minnesota man guilty in fatal stabbing of teen on Wisconsin river, jury finds

- Wisconsin teen sentenced in bonfire explosion that burned at least 17

- Wisconsin man who broke into home, ate victim’s chicken, slept in victim’s bed, receives prison and jail sentences

- Judge refuses to dismiss Hunter Biden’s gun case

- House passes reauthorization of key US surveillance program after days of upheaval over changes

- Milwaukee Police officer traveling to Georgia training retires before facing discipline

- Evers to ask legislature to approve largest increase in state support for UW System in two decades

- 7th Circuit Court of Appeals proposes new rules

- Federal agencies allege toxic work environment for women in new report

- Wisconsin man sentenced for sex trafficking a woman and a minor online

WLJ People

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Russell Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Benjamin Nicolet

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dustin T. Woehl

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Katherine Metzger

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Joseph Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – James M. Ryan

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Dana Wachs

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Mark L. Thomsen

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Matthew Lein

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Jeffrey A. Pitman

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – William Pemberton

- Power 30 Personal Injury Attorneys – Howard S. Sicula